One of the central concerns about Britain leaving the European Union is that it will put British jobs at risk. How many jobs, precisely? Or, if not precisely, then at least roughly?

For clarification on this burning issue of our time, naturally I turned to the acknowledged expert on economics in modern politics, the man who spent ten years as chancellor of the exchequer before becoming prime minister.

During the 1997 election campaign, Gordon Brown warned that divisions and uncertainty in the Conservative Party threatened 'the three-and-a-half million jobs that relied on Europe'. But that seems to have been an over-estimate, because four years later he was arguing that 'over three quarters of a million UK companies trade with the rest of the European Union - half our total trade - with three million jobs affected'.

So it's three million? Yes, that must be right. Because that was the figure Brown was still citing in 2005, and then again in the 2010 election campaign: 'Three million jobs depend on our membership of the European Union.'

And in March this year, Brown made the same point: 'We must tell the truth about the three million jobs, 25,000 companies, £200 billion of annual exports and the £450 billion of inward investment linked to Europe.'

(Incidentally, that '25,000 companies' is a bit worrying, don't you think? In 2001 it was 'over three quarters of a million companies'. What on earth has happened to our economy?)

Coming back to those three million jobs, though. It's not just Gordon Brown who quotes this figure. It's bandied around all the time by those who support British membership of the EU. It was quoted, for example, by Tim Farron on Question Time last night.

But I'm no economist, and there's something I don't fully understand. We had, we were told, the longest period of uninterrupted growth in our history, followed by the worst recession in living memory, and then a recovery that's either the envy of the developed world or a fragile property-fuelled bubble (depending on taste).

Things have changed so much. Back in 1997 we had around 26 million people employed in Britain. Now it's over 30 million.

And yet somehow, inexplicably, the number of jobs dependent on the EU doesn't seem to have moved an inch in all that time. It didn't go up in the good times; it hasn't come down with all the problems in the Euro-zone.

It just sits there, unchanging and - perhaps more to the point - unchallenged. Puzzling, isn't it?

Showing posts with label Question Time. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Question Time. Show all posts

Friday, 22 May 2015

Wednesday, 6 May 2015

The general election campaign, 2015

Possibly the sheer resilience of Nick Clegg, the thickest-skinned politician ever. Probably Natalie Bennett, with her brain-fades and advocacy of polyamorous marriages. Definitely Grant Shapps in all his gormless glory.

What else? Russell Brand would be in there. Maybe Ed Miliband and the hen party? Maybe David Cameron forgetting which football club he's supposed to support? That's the kind of thing I normally record.

The one event that would certainly be included - even though it'll fade from the collective memory - would be the BBC Question Time last week, in which the audience accused successively Miliband, Cameron and Clegg of being liars. More than anything else, that seemed to nail this campaign and the state of modern politics.

Before, during and after the manifesto launches, we've had - from all parties - a relentless series of what columnists nowadays like to call 'offers', but which we used to call policies. Or bribes, to be more precise. Each day there's been a new proposal to reduce tax or to increase spending or, more frequently, to tell other people what things they should be doing differently.

Employers, housing associations, landlords, fuel companies, rail operators, bankers, tobacco firms: all of them, ministers manqué claim, could be regulated more stringently or made to reduce their profitability. This is all perfectly fine and legitimate - only the libertarian fringes object on principle to all intervention in 'the market' - but it's hard not to see it as being an alternative to government action.

One party suggests they'll build x number of houses, and another chips in with x x 2 (or x x 3, if x x 2 has already been taken). None of the contenders actually intend to build any houses themselves, of course: these are just figures plucked out of thin air and magically transformed into targets.

Because we are still, sadly, in a political world of targets. Lord know it's not as bad as during the first government of Tony Blair when, as I wrote in my book A Classless Society:

There were targets for the quantity of cars, cycles and pedestrians on the road, as well as for traffic casualties and dog mess; for the numbers of smokers, heroin addicts and pregnant teenagers; for the incidence of robberies and building-fires; for how many children visited museums and galleries, and for the proportion of school-leavers going on to higher education. There was even a target for the number of otters to be found in the wild...But even without this excess of zeal, the thinking behind the target culture still dominates political thinking; the stated intention to do something is believed to be just as good - and certainly much easier - than actually doing it. As Blair himself once put it: 'It's the signals that matter, not the policy.'

This time the signals extend to cover the behaviour of foreigners.

The Tory manifesto promises to deliver '100,000 more UK companies exporting in 2020 than in 2010' with a 'target of £1 trillion in exports' - presumably whether or not people want to buy our stuff.

It also says: 'We will set challenging targets for Visit Britain and Visit England to ensure more visitors travel outside the capital' - whether or not that was in the holiday plans made by those tourists.

Meanwhile, the Labour manifesto promises to 'push for global targets to tackle inequality and promote human rights' - whether or not... well, you get the idea on that one.

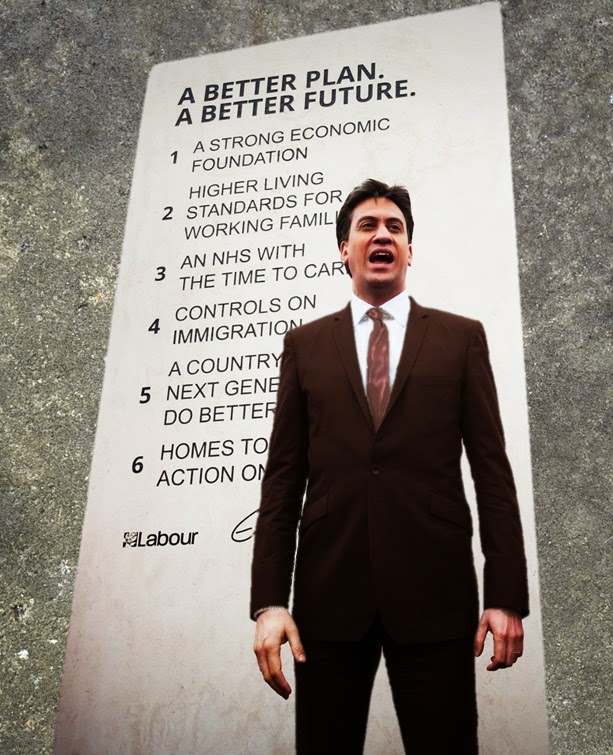

And since we don't believe these silly statements, however solemnly intoned they are, we then get the absurd spectacle of Cameron pledging to enshrine in law a promise not to increase income tax, VAT or national insurance. Followed by the even more absurd Miliband gimmick of having his vague, waffly pledges literally carved in stone.

I genuinely thought that this last one was a joke when I heard it. I still do.

But no matter how feverish the promises, how apocalyptic the denunciations of the other side(s), the electorate - as that Question Time audience illustrated - resolutely refuses to be convinced. We still think they're all lying. And they are.

Just to be clear: this was not always the case. There was a time when politicians told us grown-ups if things were going wrong. This is Edward Heath's message to the country in December 1973, telling us that we were in for the hardest Christmas since the war and that our standard of living was going to fall:

I'm not sure I can envisage Cameron or Miliband making that kind of broadcast.

Mind you, it didn't do Heath much good; two months later, he was thrown out of office. Maybe that's why telling the truth fell out of fashion. Or maybe it was John Smith as shadow chancellor in 1992, telling us that if we wanted better services - which we said we did - we would have to see tax rises, which we decided was beyond the pale. Or possibly it was Blair winning three consecutive elections by peddling his PFI fantasy of 'investment' on the never-never.

In any event, everyone now knows that there are serious problems coming, yet no politician is prepared to say so.

Despite all of which, I remain mostly optimistic about the future.

Primarily this is because I don't believe the current settlement can survive, since it is so clearly dysfunctional.

As many have pointed out, the principal justification for a first-past-the-post electoral system has always been that it provides strong, stable government. This no longer looks like a clinching argument.

The inherent distortions are about to be revealed in the starkest manner ever. It is almost certain that Ukip will win the third largest share of the vote, and yet could end up tenth in the share of seats (the position it was in at the dissolution of the last Parliament).

Similarly, Nicola Sturgeon has talked a great deal about 'shutting the Tories out of Downing Street' with an anti-Tory majority in the Commons. This may well be the result, but the majority of the popular vote is likely at the same time to be right-of-centre; the Conservatives, Ukip and the Liberal Democrats will probably get more than 50 per cent between them. (I'm assuming that the Lib Dems' more left-inclined supporters will have abandoned them.)

There is also the fact that we no longer have any national parties, just a fraying patchwork of regional and nationalist groups. Those that still pretend to be national are self-evidently not fit for purpose.

And then there's Scotland. Some commentators are berating the Conservatives for jeopardising the Union with their apparent encouragement of the Scottish National Party; others are berating the Labour Party for their complacency in letting the SNP outflank them on the left.

But it doesn't matter much who's to blame; the fact is that there aren't very many passionate Unionists left, on either side of the border. Those who do claim to believe in the Union seem incapable of making out a case for it that goes beyond sentiment and slogan.

Whatever happens tomorrow, large numbers of people are going to feel not merely unhappy - that's normal - but cheated.

Back in 2012, I wrote that 'things are about to change quite radically'. I think we're edging ever nearer a critical moment.

Friday, 1 May 2015

...like the leaving of it

Seven days from now, we may well be getting the first resignation of a party leader. Presumably the Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party of England and Wales will stick with their incumbent leaders, but for the others, nothing is certain. Quite possibly Nigel Farage and/or Nick Clegg will fail to be elected in the first place, while either David Cameron or Ed Miliband - whichever doesn't get to be prime minister - won't be long for the leadership.

As an object lesson in how not to leave the job of party leader, you'd have to go a long way to beat Gordon Brown.

Following the indecisive result of the general election in 2010, he hung around in Downing Street for a few days - as he was constitutionally bound to do, since he was still prime minister - but then abruptly walked out, a few hours before the deal between Cameron and Clegg was concluded: and on that he was constitutionally wrong.

The real problem, though, was what followed. Brown resigned the Labour leadership and sulked off to Scotland, leaving Harriet Harman to mind the shop for the next few months while the long process of choosing a new leader played itself out. It was during that period that the narrative of the financial crash and crisis was firmly fixed in the public consciousness by the coalition government.

Brown was badly damaged by then, but he should still have been capable of articulating an alternative view, of defending the economic growth figures bequeathed to the new government. He didn't do so. And the legacy of Brown's self-indulgence could be seen on Question Time last night, as Ed Miliband squirmed in the face of questions on Labour's economic record. The ground lost in 2010 has never been recovered.

Compare and contrast Michael Howard departure from the Conservative Party leadership in 2005. He announced immediately after losing the election that he would be standing down, but not for another six months, not till a new leader had been chosen. He then reshuffled his front-bench team and promoted George Osborne to shadow chancellor and David Cameron to shadow education secretary, thereby setting up the new generation to inherit the leadership. It worked perfectly (though Howard would probably have preferred Osborne).

It is possible in retrospect to conclude that Howard didn't ultimately do his party any favours in the short term, that David Davis would have been a sounder choice in 2005 and might well have won a majority in 2010. But even if one accepted this, Howard was at least doing what he genuinely believed was in his party's interests. Unlike Brown, who simply abandoned his party.

As an object lesson in how not to leave the job of party leader, you'd have to go a long way to beat Gordon Brown.

Following the indecisive result of the general election in 2010, he hung around in Downing Street for a few days - as he was constitutionally bound to do, since he was still prime minister - but then abruptly walked out, a few hours before the deal between Cameron and Clegg was concluded: and on that he was constitutionally wrong.

The real problem, though, was what followed. Brown resigned the Labour leadership and sulked off to Scotland, leaving Harriet Harman to mind the shop for the next few months while the long process of choosing a new leader played itself out. It was during that period that the narrative of the financial crash and crisis was firmly fixed in the public consciousness by the coalition government.

Brown was badly damaged by then, but he should still have been capable of articulating an alternative view, of defending the economic growth figures bequeathed to the new government. He didn't do so. And the legacy of Brown's self-indulgence could be seen on Question Time last night, as Ed Miliband squirmed in the face of questions on Labour's economic record. The ground lost in 2010 has never been recovered.

Compare and contrast Michael Howard departure from the Conservative Party leadership in 2005. He announced immediately after losing the election that he would be standing down, but not for another six months, not till a new leader had been chosen. He then reshuffled his front-bench team and promoted George Osborne to shadow chancellor and David Cameron to shadow education secretary, thereby setting up the new generation to inherit the leadership. It worked perfectly (though Howard would probably have preferred Osborne).

It is possible in retrospect to conclude that Howard didn't ultimately do his party any favours in the short term, that David Davis would have been a sounder choice in 2005 and might well have won a majority in 2010. But even if one accepted this, Howard was at least doing what he genuinely believed was in his party's interests. Unlike Brown, who simply abandoned his party.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)