Showing posts with label Tony Blair. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Tony Blair. Show all posts

Sunday, 23 August 2015

In addition to my duties in this House

I shall continue writing this blog, but recently I've also started putting together another site, Lion & Unicorn, to which I would like to draw your attention.

This is still at an early stage, but I have high hopes for the venture. The intention is cover aspects of England and Britain - political, cultural, economic, sporting - in a slightly more reflective manner than the media generally has time to do.

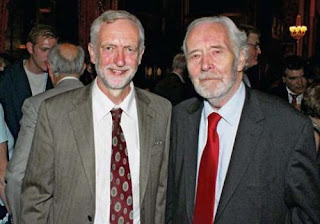

Which doesn't mean that it will avoid the news agenda entirely. So, for example, there are currently to be found several pieces that explore aspects of this season's excitement, Jeremy Corbynmania. Sam Harrison writes about who or what is responsible for Corbynmania, Dan Atkinson examines Corbyn's policy of people's quantitative easing, and I blame Tony Blair for his lack of faith in politics. I also engage in a little light mockery of the whole phenomenon.

As I say, early days yet, and we haven't officially launched the site (whatever we mean by that), but it's starting to come together. Lion & Unicorn - bookmark it, bear it in mind. Now you know where we are, don't be a stranger.

Wednesday, 19 August 2015

Human till she talks: a portrait of Yvette Cooper

One of the standard jokes at the start of the current Labour leadership election was that Yvette Cooper's judgement has to be suspect: after all, she did marry Ed Balls. Not very funny, I know, and also deeply unfair, because on the plus side they chose Eastbourne for their wedding, she wore Vivienne Westwood for the ceremony, and they went to Euro-Disney for their honeymoon. Which deals with the lack of judgement charge.

In general, of course, it's unfair to reflect on a politician's partner, but in the case of the first husband and wife team to serve in a British cabinet, it's kind of inevitable. For nearly two decades, they've been seen as a single force. As a magazine pointed out in 1998, Cooper and Balls were 'New Labour's It Couple, the zenith of everything it stands for.' A Daily Telegraph profile of the pair the same year was headlined: 'Will this couple make it to Number 10?' Or, as the Guardian put it, they were 'the Posh and Becks of the Labour Party'.

Born in 1969, Yvette Cooper studied PPE at Oxford and went on to become an adviser to John Smith and to Harriet Harman. (My apologies for the repetitions in this series of portraits, but there really is a shocking lack of variation in the backgrounds of the candidates.)

She also worked for a while in journalism, as a leader writer and as the economics correspondent for the Independent. She was perfectly okay, and occasionally wandered out of her field. This is her on the supposed crisis in masculinity that was such a big media deal in the 1990s:

Her articles tended to be broadly supportive of the Labour Party in opposition, but even she struggled to put a positive gloss on Tony Blair at times, and had to concede that his borrowing of Will Hutton's 'stakeholding' concept was little more than, in her word, 'waffly'.

Her ambitions, however, lay in Parliament not Fleet Street. Under the patronage of Gordon Brown, she attempted to become the candidate for the safe seat of Don Valley, where she lost out to Caroline Flint, before securing the nomination for the even safer Pontefract & Castleford, where she beat both Hilary Benn and Derek Scott (Tony Blair's economic adviser, who later wrote Off Whitehall).

She was one of ten Labour MPs elected in the 1997 landslide who were still in their twenties, and was clearly marked out for early advancement.

When Brown announced that he was handing over control of interest rates to the Bank of England, it was Cooper - just four days into her parliamentary career - who was sent onto Newsnight to defend the move to Jeremy Paxman. 'With that one step,' she wrote, 'the government has done more to achieve economic stability than anything any British government has done for years.' She brushed aside suggestions that the move was an affront to democracy: in characteristic New Labour style, managerialism was more important than politics.

Shortly after the election, Cooper and Balls - the archetypal North London couple - moved from Hackney to the New Labour heartland of Islington, though they later moved again, this time to upwardly mobile Stoke Newington. For expenses purposes, this was, of course, their second home, entitling them to a subsidised mortgage. When such things began to provoke outrage, it was reported that between them they had 'racked up more than £300,000 in expenses' in 2006-07, considerably above the national average for MPs.

From a whip's perspective, her behaviour in Parliament was exemplary, largely - one suspects - because she was a genuine believer in the Blair-Brown 'project'. The Demon Ears column in the Observer concluded that she 'isn't that bad for a New Labour MP, even though she does dream on message'.

By October 1998 she was being offered a minor government post, though she turned it down in favour of remaining a member of the intelligence and security committee. It proved to be only a short delay: the following year she took on the public health portfolio, becoming the youngest minister in Blair's administration. She then went on to become the first minister to say she'd once smoked pot and, admirably, didn't claim not to have liked it: 'I did try cannabis while at university, like a lot of students at that time, and it is something that I have left behind.'

In her new role she was partly responsible for the cross-departmental project Sure Start, widely seen as one of the better initiatives of New Labour. Its fanbase was wide enough to include, slightly oddly, a children's TV favourite: 'Peppa Pig is a well-known fan of Sure Start children's centres,' it was revealed in 2010.

Less successful was the idea of a crusade against teenage pregnancies under the slogan 'It's OK to be a virgin'. Cooper had sufficient political nous to reject that in favour of 'a straightforward campaign which gives teenagers the facts and is aimed as much at boys as at girls'.

Less successful was the idea of a crusade against teenage pregnancies under the slogan 'It's OK to be a virgin'. Cooper had sufficient political nous to reject that in favour of 'a straightforward campaign which gives teenagers the facts and is aimed as much at boys as at girls'.

She moved to the Lord Chancellor's department in 2002, then to environment, transport and the regions, where she became minister of state for housing and planning.

The latter portfolio did not count among New Labour's great achievements: during Blair and Brown's period in office, an average of 562 council homes were built each year, compared to the annual average of 41,343 during Margaret Thatcher's premiership.

Cooper did little to improve this woeful record, but she did do some things. She relaxed the regulations on householders installing small windmills and solar panels, and she piloted the chaotic introduction of Home Information Packs. She also faced criticism for allowing more house-building on flood plains. And she suggested that middle-aged couples in social housing should be encouraged to move out of cities when their children left home, to free up housing stock. Her concern here was over 'underoccupied' social housing, an issue later addressed - in somewhat more heavy-handed manner - by the Coalition government's bedroom tax.

When Gordon Brown became prime minister, she remained as housing minister but was given a new right to attend cabinet meetings, and then, in 2008, she made the cabinet proper as chief secretary to the Treasury. Just in time for the credit crunch, though happily she didn't stay very long. As Brown's government descended into a farce of resignations, her loyalty was rewarded with a further promotion, and she served out the rest of the New Labour years as work and pensions secretary, inheriting the agenda set by her predecessor James Purnell.

She spent most of the Ed Miliband era as shadow home secretary, one of the easiest jobs in politics, since there's always something going wrong in the Home Office to provide you with ammunition. This was, famously, where Tony Blair had made his name in 1992-94 in his 'tough on crime' days. But Cooper failed completely to make the same kind of impact and was largely invisible. 'Home secretary Theresa May was fighting for her political life last night as she was engulfed by the border checks scandal,' read the papers in 2011, but Cooper failed to exploit the situation, and of the two you'd probably bet on May being the one to make it to prime minister.

Perhaps, though, that job was a waste of her talent, which is much more obviously focussed on the economy. As shadow chancellor, she would have made a trickier opponent for George Osborne than did her husband.

Beyond economic matters, there has been much talk of women's issues, though sometimes this has been seen as being somewhat narrow in scope. Arguing, for example, in support of cuts to single-parent benefits in 1997, she displayed little interest in those who wished to concentrate on parenthood: 'It's a question of priorities. If we put resources into childcare and helping people back to work, we will raise the standard of living for the poorest.'

Similarly, she has repeatedly claimed over the last few years that 'David Cameron has a real problem with women'. This is an over-simplification, seeming to imply that women can be seen as a homogenous, metropolitan, professional block, somewhat in the image of Cooper herself.

The reality is that age is as big a factor as gender. At the election this year, according to Ipsos-Mori, Labour had a 20-percentage-point lead over the Conservatives among women aged 18-24, but trailed by 18 points among women over the age of 55. Unfortunately for Labour, which clearly has a real problem with older women, there are considerably more of them, and they're more likely to vote.

Cooper considered standing for the leadership in 2010, and Balls said that if she did so, he wouldn't stand himself. She decided against it, however, because she wanted to spend more time with her children. Five years on, and it was inevitable that she would be a candidate. By any normal standards, she really ought to be the front-runner, the one that the others have to beat. But that's not how it's worked out.

In 1997 she condemned - with complete justification - the Conservatives for their remoteness: 'They took politics far away from normal people's lives.' She points, with some justification, to Sure Start as her contribution to changing that, but as a politician, she herself doesn't seem to connect. There's something that isn't quite right. Perhaps Simon Hattenstone put his finger on it in the Guardian in 2010. 'It's funny that Cooper seems so human till she starts to talk,' he wrote, 'while Balls seems so monstrous till he starts.'

This is the third in a series of profiles of the four candidates in the Labour Party leadership election. Yesterday: Liz Kendall. Tomorrow: Jeremy Corbyn.

In general, of course, it's unfair to reflect on a politician's partner, but in the case of the first husband and wife team to serve in a British cabinet, it's kind of inevitable. For nearly two decades, they've been seen as a single force. As a magazine pointed out in 1998, Cooper and Balls were 'New Labour's It Couple, the zenith of everything it stands for.' A Daily Telegraph profile of the pair the same year was headlined: 'Will this couple make it to Number 10?' Or, as the Guardian put it, they were 'the Posh and Becks of the Labour Party'.

Born in 1969, Yvette Cooper studied PPE at Oxford and went on to become an adviser to John Smith and to Harriet Harman. (My apologies for the repetitions in this series of portraits, but there really is a shocking lack of variation in the backgrounds of the candidates.)

She also worked for a while in journalism, as a leader writer and as the economics correspondent for the Independent. She was perfectly okay, and occasionally wandered out of her field. This is her on the supposed crisis in masculinity that was such a big media deal in the 1990s:

The only thing these men really have to adjust to is change itself. No, they can't have a job for life anymore. But so what? Few women ever had one. And no, they can't invest their entire identity in the firm they work for: the company might not be there in two years. And if they are too frit to visit their GPs they had better reconcile themselves to early avoidable death.No tolerance for the nanny state here, then; you sink or swim according to your own efforts.

Her articles tended to be broadly supportive of the Labour Party in opposition, but even she struggled to put a positive gloss on Tony Blair at times, and had to concede that his borrowing of Will Hutton's 'stakeholding' concept was little more than, in her word, 'waffly'.

Her ambitions, however, lay in Parliament not Fleet Street. Under the patronage of Gordon Brown, she attempted to become the candidate for the safe seat of Don Valley, where she lost out to Caroline Flint, before securing the nomination for the even safer Pontefract & Castleford, where she beat both Hilary Benn and Derek Scott (Tony Blair's economic adviser, who later wrote Off Whitehall).

She was one of ten Labour MPs elected in the 1997 landslide who were still in their twenties, and was clearly marked out for early advancement.

When Brown announced that he was handing over control of interest rates to the Bank of England, it was Cooper - just four days into her parliamentary career - who was sent onto Newsnight to defend the move to Jeremy Paxman. 'With that one step,' she wrote, 'the government has done more to achieve economic stability than anything any British government has done for years.' She brushed aside suggestions that the move was an affront to democracy: in characteristic New Labour style, managerialism was more important than politics.

Shortly after the election, Cooper and Balls - the archetypal North London couple - moved from Hackney to the New Labour heartland of Islington, though they later moved again, this time to upwardly mobile Stoke Newington. For expenses purposes, this was, of course, their second home, entitling them to a subsidised mortgage. When such things began to provoke outrage, it was reported that between them they had 'racked up more than £300,000 in expenses' in 2006-07, considerably above the national average for MPs.

From a whip's perspective, her behaviour in Parliament was exemplary, largely - one suspects - because she was a genuine believer in the Blair-Brown 'project'. The Demon Ears column in the Observer concluded that she 'isn't that bad for a New Labour MP, even though she does dream on message'.

By October 1998 she was being offered a minor government post, though she turned it down in favour of remaining a member of the intelligence and security committee. It proved to be only a short delay: the following year she took on the public health portfolio, becoming the youngest minister in Blair's administration. She then went on to become the first minister to say she'd once smoked pot and, admirably, didn't claim not to have liked it: 'I did try cannabis while at university, like a lot of students at that time, and it is something that I have left behind.'

In her new role she was partly responsible for the cross-departmental project Sure Start, widely seen as one of the better initiatives of New Labour. Its fanbase was wide enough to include, slightly oddly, a children's TV favourite: 'Peppa Pig is a well-known fan of Sure Start children's centres,' it was revealed in 2010.

Less successful was the idea of a crusade against teenage pregnancies under the slogan 'It's OK to be a virgin'. Cooper had sufficient political nous to reject that in favour of 'a straightforward campaign which gives teenagers the facts and is aimed as much at boys as at girls'.

Less successful was the idea of a crusade against teenage pregnancies under the slogan 'It's OK to be a virgin'. Cooper had sufficient political nous to reject that in favour of 'a straightforward campaign which gives teenagers the facts and is aimed as much at boys as at girls'.She moved to the Lord Chancellor's department in 2002, then to environment, transport and the regions, where she became minister of state for housing and planning.

The latter portfolio did not count among New Labour's great achievements: during Blair and Brown's period in office, an average of 562 council homes were built each year, compared to the annual average of 41,343 during Margaret Thatcher's premiership.

Cooper did little to improve this woeful record, but she did do some things. She relaxed the regulations on householders installing small windmills and solar panels, and she piloted the chaotic introduction of Home Information Packs. She also faced criticism for allowing more house-building on flood plains. And she suggested that middle-aged couples in social housing should be encouraged to move out of cities when their children left home, to free up housing stock. Her concern here was over 'underoccupied' social housing, an issue later addressed - in somewhat more heavy-handed manner - by the Coalition government's bedroom tax.

When Gordon Brown became prime minister, she remained as housing minister but was given a new right to attend cabinet meetings, and then, in 2008, she made the cabinet proper as chief secretary to the Treasury. Just in time for the credit crunch, though happily she didn't stay very long. As Brown's government descended into a farce of resignations, her loyalty was rewarded with a further promotion, and she served out the rest of the New Labour years as work and pensions secretary, inheriting the agenda set by her predecessor James Purnell.

She spent most of the Ed Miliband era as shadow home secretary, one of the easiest jobs in politics, since there's always something going wrong in the Home Office to provide you with ammunition. This was, famously, where Tony Blair had made his name in 1992-94 in his 'tough on crime' days. But Cooper failed completely to make the same kind of impact and was largely invisible. 'Home secretary Theresa May was fighting for her political life last night as she was engulfed by the border checks scandal,' read the papers in 2011, but Cooper failed to exploit the situation, and of the two you'd probably bet on May being the one to make it to prime minister.

Perhaps, though, that job was a waste of her talent, which is much more obviously focussed on the economy. As shadow chancellor, she would have made a trickier opponent for George Osborne than did her husband.

Beyond economic matters, there has been much talk of women's issues, though sometimes this has been seen as being somewhat narrow in scope. Arguing, for example, in support of cuts to single-parent benefits in 1997, she displayed little interest in those who wished to concentrate on parenthood: 'It's a question of priorities. If we put resources into childcare and helping people back to work, we will raise the standard of living for the poorest.'

Similarly, she has repeatedly claimed over the last few years that 'David Cameron has a real problem with women'. This is an over-simplification, seeming to imply that women can be seen as a homogenous, metropolitan, professional block, somewhat in the image of Cooper herself.

The reality is that age is as big a factor as gender. At the election this year, according to Ipsos-Mori, Labour had a 20-percentage-point lead over the Conservatives among women aged 18-24, but trailed by 18 points among women over the age of 55. Unfortunately for Labour, which clearly has a real problem with older women, there are considerably more of them, and they're more likely to vote.

Cooper considered standing for the leadership in 2010, and Balls said that if she did so, he wouldn't stand himself. She decided against it, however, because she wanted to spend more time with her children. Five years on, and it was inevitable that she would be a candidate. By any normal standards, she really ought to be the front-runner, the one that the others have to beat. But that's not how it's worked out.

In 1997 she condemned - with complete justification - the Conservatives for their remoteness: 'They took politics far away from normal people's lives.' She points, with some justification, to Sure Start as her contribution to changing that, but as a politician, she herself doesn't seem to connect. There's something that isn't quite right. Perhaps Simon Hattenstone put his finger on it in the Guardian in 2010. 'It's funny that Cooper seems so human till she starts to talk,' he wrote, 'while Balls seems so monstrous till he starts.'

This is the third in a series of profiles of the four candidates in the Labour Party leadership election. Yesterday: Liz Kendall. Tomorrow: Jeremy Corbyn.

Tuesday, 18 August 2015

Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition

The word that keeps coming up in the profiles I'm writing of the Labour candidates is 'loyal'. Of the nine candidates for the leadership and deputy leadership, eight have repeatedly been described as loyal. And in this context, loyalty means voting as the whips tell you. By contrast, the ninth candidate is Jeremy Corbyn, best known for ignoring the party whip on hundreds of occasions, and therefore being disloyal.

But this is a very limited version of loyalty. Traditionally, it was loyalty to the party that was cherished, rather than simply walking into the right lobby at Westminster. And, traditionally, it's been the political right that has been far less loyal than has the left or the trade unions.

The clearest example was the creation of the SDP in 1981, led by Roy Jenkins (who'd previously led the great parliamentary rebellion to ensure British entry into the European Community). When the right had control of the party, the left went along with it, even if they did grumble and moan. As soon as the left seemed to be in the ascendancy, the intellectual right split from Labour altogether.

The arrival of the New Labour right added a new dimension. Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Peter Mandelson simply plotted endlessly. Blair tried to get John Smith to stage a leadership coup against Neil Kinnock. Then, when Smith did become leader, Blair and Mandelson schemed against him as well. And eventually, they all descended into plotting against each other. Despite the supposed iron discipline of New Labour, there was no loyalty at all to individuals, leaders or the party.

Jeremy Corbyn, on the other hand, has been an MP for thirty-two years, for perhaps thirty of which he has been in a beleaguered minority. He may not have always done what he was told, but he never threatened to leave if he didn't get his own way, and he has never (as far as I'm aware) plotted to stage a coup against the leadership.

This is relevant, of course, in terms of the current leadership election. Should anyone but Corbyn win, there will be demands for unity, discipline and loyalty. Should Corbyn win, don't expect the right to display any loyalty whatsoever.

But this is a very limited version of loyalty. Traditionally, it was loyalty to the party that was cherished, rather than simply walking into the right lobby at Westminster. And, traditionally, it's been the political right that has been far less loyal than has the left or the trade unions.

The clearest example was the creation of the SDP in 1981, led by Roy Jenkins (who'd previously led the great parliamentary rebellion to ensure British entry into the European Community). When the right had control of the party, the left went along with it, even if they did grumble and moan. As soon as the left seemed to be in the ascendancy, the intellectual right split from Labour altogether.

The arrival of the New Labour right added a new dimension. Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Peter Mandelson simply plotted endlessly. Blair tried to get John Smith to stage a leadership coup against Neil Kinnock. Then, when Smith did become leader, Blair and Mandelson schemed against him as well. And eventually, they all descended into plotting against each other. Despite the supposed iron discipline of New Labour, there was no loyalty at all to individuals, leaders or the party.

Jeremy Corbyn, on the other hand, has been an MP for thirty-two years, for perhaps thirty of which he has been in a beleaguered minority. He may not have always done what he was told, but he never threatened to leave if he didn't get his own way, and he has never (as far as I'm aware) plotted to stage a coup against the leadership.

This is relevant, of course, in terms of the current leadership election. Should anyone but Corbyn win, there will be demands for unity, discipline and loyalty. Should Corbyn win, don't expect the right to display any loyalty whatsoever.

You don't give up: a portrait of Liz Kendall

When Liz Kendall was asked recently if she would step down from the Labour leadership election in an attempt to unify the anti-Jeremy Corbyn forces, she bristled at the very suggestion. 'You don't give up fighting for what you believe in,' she insisted. 'I love the party too much to see us lose again.' The echoes of Hugh Gaitskell's 'Fight, fight and fight again' were presumably not unconscious.

Born in 1971, Liz Kendall (not to be confused with the similarly named girlfriend of American serial killer Ted Bundy) studied history at Cambridge. She then followed the conventional path and - like David Miliband and James Purnell - went to work for the Institute for Public Policy Research, one of the many left-wing think tanks of the time that between them produced more ministers manqué than government initiatives.

While there, she co-wrote a 1994 pamphlet on the virtue of citizens' juries, a kind of state-approved focus group that would 'bring the voice and experience of ordinary citizens into the political process'. It was a neat idea for expanding democracy, borrowed from Germany, but of course it never materialised, and I can't find a reference to it in the last twenty years.

As soon as Labour was elected in 1997, she was recruited to become a special adviser (alongside John McTernan) to Harriet Harman at the department of social security, where she concentrated 'on women's issues especially lone mothers'. Unfortunately, it was a cut to single parent benefits, ordered by Downing Street, that precipitated the first great rebellion of the Tony Blair government, and cost Harman her job. Kendall left Whitehall at the same time and went back to the IPPR and to work in the charity sector.

She was put on the national list of candidates, but failed to secure the nomination to succeed Tony Benn in Chesterfield, where the Labour candidate was, said the Guardian, 'virtually guaranteed a seat in Parliament' in the 2001 election. (Actually it fell to the Liberal Democrats.)

She moved on to the charity Maternity Alliance and became in due course a special adviser to the health secretary, Patricia Hewitt, perhaps the only politician to be name-checked in a David Bowie song (in 'The Gospel According to Tony Day', the 1967 B-side to 'The Laughing Gnome').

She moved on to the charity Maternity Alliance and became in due course a special adviser to the health secretary, Patricia Hewitt, perhaps the only politician to be name-checked in a David Bowie song (in 'The Gospel According to Tony Day', the 1967 B-side to 'The Laughing Gnome').

In 2010 she was finally elected to the House of Commons, taking over Hewitt's old seat in Leicester West. She was thirty-eight, which by New Labour standards was getting on a bit, but she was singled out by John Curtice in the Sunday Telegraph as one of the party's rising stars of the new Parliament, along with Tristram Hunt, Rachel Reeves, Chuka Umuna and Gloria De Piero.

She did have a position under Ed Miliband, as shadow spokesperson for care and older people, but you'd be hard pushed to notice her make any public impact. Nonetheless, when Miliband resigned following his election disaster in May, she was the first to declare her candidacy, the speed of her decision seeming to wrongfoot others who might be considered to be on the Blairite wing of the party.

She herself, for obvious reasons, tends to disown the Blairite tag, but there is something in it. As Blair himself admitted, he never came close to completing his public sector reforms, to achieving a reorientation towards users; Kendall talks a strong case on the subject. She's also spoken of the need to meet the Nato target of 2 per cent of GDP to be allocated to defence. And she's almost as harsh on Jeremy Corbyn as Blair himself, suggesting that, even if he were to win the leadership, she wouldn't want to see him as prime minister.

The implication of that, of course, is that she would rather see a Conservative government than a Corbynite Labour one. And that has attracted a great deal of abuse from the left. It is, though, a legitimate argument for any but the most tribal. If you believe that it is essential to have a strong economy in order to provide public services, and if you believe that Corbyn would severely damage the nation's economy, then it is logical to conclude that you'd rather wait your turn, in the expectation that there would still be something worth taking over in five years time.

If that seems silly, then it's indicative of the foolishness of the current party alignment. Somewhere, in a parallel universe, the Tories lost the general election badly and Bill Cash is currently the front-runner to become Conservative leader. He's a man of principle, not afraid to speak his mind, offers hope for the future, at least you know what he believes in etc etc. And Ken Clarke and Michael Heseltine are issuing statements that he'd rather see a pro-EU Labour government than for their own party to win under Cash.

Since her abrupt arrival on centre stage, Kendall has been profiled often enough in the papers for us to learn that she went to school with Geri Halliwell, that she's a fan of Public Enemy, Dr Dre and Eminem, that's she's a keen runner, and that she had a lengthy relationship with the comedian Greg Davies. None of which has done a single thing to project a personality, or to change the public perception of her as something of an enigma: someone who clearly wishes to be the leader, but exhibits no obvious sign of leadership.

In person, it's acknowledged, she is warm and charismatic. (Mind you, that's what they always said about Ed Miliband, as well.) She is also reckoned to be extremely determined, steely and committed, though this hasn't come across at all in the hustings thus far. Presumably, however, it explains why she considered it appropriate to stand for the leadership at all, with only five years in Parliament behind her and no time in government.

In that lack of experience, as in much else, she resembles nothing so much as a Labour version of David Cameron. Both have the same desire to accept aspects of the modern world that don't sit easily with traditionalists in their parties, in her case in relation to the public sector and social security. And perhaps if Kendall were in the same position as Cameron in 2005 - if her party were coming off the back of three election defeats, rather than just the two - she might have been better heard and made more impact.

But that's not where Labour is right now and, though she may well be back, it wouldn't be surprising if she left Parliament altogether. She could probably have far more impact campaigning outside than she would in a shadow cabinet led by Yvette Cooper, and certainly more than she would grimacing on the backbenches behind Jeremy Corbyn.

In 1974 Margaret Stewart wrote a fine book titled Protest or Power? A Study of the Labour Party. In that divide, there is little doubt about which side Kendall stands on.

This is the second in a series of profiles of the four candidates in the Labour Party leadership election. Yesterday: Andy Burnham. Tomorrow: Yvette Cooper.

Born in 1971, Liz Kendall (not to be confused with the similarly named girlfriend of American serial killer Ted Bundy) studied history at Cambridge. She then followed the conventional path and - like David Miliband and James Purnell - went to work for the Institute for Public Policy Research, one of the many left-wing think tanks of the time that between them produced more ministers manqué than government initiatives.

While there, she co-wrote a 1994 pamphlet on the virtue of citizens' juries, a kind of state-approved focus group that would 'bring the voice and experience of ordinary citizens into the political process'. It was a neat idea for expanding democracy, borrowed from Germany, but of course it never materialised, and I can't find a reference to it in the last twenty years.

As soon as Labour was elected in 1997, she was recruited to become a special adviser (alongside John McTernan) to Harriet Harman at the department of social security, where she concentrated 'on women's issues especially lone mothers'. Unfortunately, it was a cut to single parent benefits, ordered by Downing Street, that precipitated the first great rebellion of the Tony Blair government, and cost Harman her job. Kendall left Whitehall at the same time and went back to the IPPR and to work in the charity sector.

She was put on the national list of candidates, but failed to secure the nomination to succeed Tony Benn in Chesterfield, where the Labour candidate was, said the Guardian, 'virtually guaranteed a seat in Parliament' in the 2001 election. (Actually it fell to the Liberal Democrats.)

She moved on to the charity Maternity Alliance and became in due course a special adviser to the health secretary, Patricia Hewitt, perhaps the only politician to be name-checked in a David Bowie song (in 'The Gospel According to Tony Day', the 1967 B-side to 'The Laughing Gnome').

She moved on to the charity Maternity Alliance and became in due course a special adviser to the health secretary, Patricia Hewitt, perhaps the only politician to be name-checked in a David Bowie song (in 'The Gospel According to Tony Day', the 1967 B-side to 'The Laughing Gnome').In 2010 she was finally elected to the House of Commons, taking over Hewitt's old seat in Leicester West. She was thirty-eight, which by New Labour standards was getting on a bit, but she was singled out by John Curtice in the Sunday Telegraph as one of the party's rising stars of the new Parliament, along with Tristram Hunt, Rachel Reeves, Chuka Umuna and Gloria De Piero.

She did have a position under Ed Miliband, as shadow spokesperson for care and older people, but you'd be hard pushed to notice her make any public impact. Nonetheless, when Miliband resigned following his election disaster in May, she was the first to declare her candidacy, the speed of her decision seeming to wrongfoot others who might be considered to be on the Blairite wing of the party.

She herself, for obvious reasons, tends to disown the Blairite tag, but there is something in it. As Blair himself admitted, he never came close to completing his public sector reforms, to achieving a reorientation towards users; Kendall talks a strong case on the subject. She's also spoken of the need to meet the Nato target of 2 per cent of GDP to be allocated to defence. And she's almost as harsh on Jeremy Corbyn as Blair himself, suggesting that, even if he were to win the leadership, she wouldn't want to see him as prime minister.

The implication of that, of course, is that she would rather see a Conservative government than a Corbynite Labour one. And that has attracted a great deal of abuse from the left. It is, though, a legitimate argument for any but the most tribal. If you believe that it is essential to have a strong economy in order to provide public services, and if you believe that Corbyn would severely damage the nation's economy, then it is logical to conclude that you'd rather wait your turn, in the expectation that there would still be something worth taking over in five years time.

If that seems silly, then it's indicative of the foolishness of the current party alignment. Somewhere, in a parallel universe, the Tories lost the general election badly and Bill Cash is currently the front-runner to become Conservative leader. He's a man of principle, not afraid to speak his mind, offers hope for the future, at least you know what he believes in etc etc. And Ken Clarke and Michael Heseltine are issuing statements that he'd rather see a pro-EU Labour government than for their own party to win under Cash.

Since her abrupt arrival on centre stage, Kendall has been profiled often enough in the papers for us to learn that she went to school with Geri Halliwell, that she's a fan of Public Enemy, Dr Dre and Eminem, that's she's a keen runner, and that she had a lengthy relationship with the comedian Greg Davies. None of which has done a single thing to project a personality, or to change the public perception of her as something of an enigma: someone who clearly wishes to be the leader, but exhibits no obvious sign of leadership.

In person, it's acknowledged, she is warm and charismatic. (Mind you, that's what they always said about Ed Miliband, as well.) She is also reckoned to be extremely determined, steely and committed, though this hasn't come across at all in the hustings thus far. Presumably, however, it explains why she considered it appropriate to stand for the leadership at all, with only five years in Parliament behind her and no time in government.

In that lack of experience, as in much else, she resembles nothing so much as a Labour version of David Cameron. Both have the same desire to accept aspects of the modern world that don't sit easily with traditionalists in their parties, in her case in relation to the public sector and social security. And perhaps if Kendall were in the same position as Cameron in 2005 - if her party were coming off the back of three election defeats, rather than just the two - she might have been better heard and made more impact.

But that's not where Labour is right now and, though she may well be back, it wouldn't be surprising if she left Parliament altogether. She could probably have far more impact campaigning outside than she would in a shadow cabinet led by Yvette Cooper, and certainly more than she would grimacing on the backbenches behind Jeremy Corbyn.

In 1974 Margaret Stewart wrote a fine book titled Protest or Power? A Study of the Labour Party. In that divide, there is little doubt about which side Kendall stands on.

This is the second in a series of profiles of the four candidates in the Labour Party leadership election. Yesterday: Andy Burnham. Tomorrow: Yvette Cooper.

Monday, 17 August 2015

A football man: a portrait of Andy Burnham

'Have you never felt the lure of sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll?' Mary Whitehouse was asked. To which she replied: 'It depends on what you mean by sex; otherwise not.'

Back in 1993-94 the Observer used to run a feature called Any Questions, in which they told us who their interviewee would be next week and invited readers to send in their queries. And, as far as I can tell, this represented Andy Burnham's first appearances in the national press, with questions to Ian Botham, Graham Gooch and indeed to the ever fascinating Mary Whitehouse.

Sadly the names weren't attached to specific queries, so we'll never know whether Burnham was the one who asked Whitehouse about sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll. Probably not. Given his love of sport, he's more likely to have been the one who asked her: 'Do you regret not having had a professional tennis career?'

Born in 1970, Andy Burnham studied English at Cambridge University and followed what was rapidly becoming the conventional path into Labour Party politics: he worked as a researcher for Tessa Jowell and as parliamentary officer for the NHS confederation, before getting a nice job administering the Football Task Force that had been set up by Tony Banks, minister of sport in Tony Blair's first government.

The aims of the Task Force were to combat racism in football, to encourage disabled access, to help 'players to act as role models in terms of behaviour and sportsmanship', and to give fans a voice, particularly in terms of 'ticketing and pricing policies that reflect the need of all on an equitable basis'. As the new Premier League season gets into its stride, you can judge their successes for yourself.

The aims of the Task Force were to combat racism in football, to encourage disabled access, to help 'players to act as role models in terms of behaviour and sportsmanship', and to give fans a voice, particularly in terms of 'ticketing and pricing policies that reflect the need of all on an equitable basis'. As the new Premier League season gets into its stride, you can judge their successes for yourself.

From there, it was but a short step to becoming a political adviser to Chris Smith, the culture secretary, and thence a safe seat in Leigh, though his parachuted arrival was not to the taste of everyone in the local party. 'This is jobs for the boys,' one member complained. 'It stinks to high heaven.'

Duly elected in 2001, he became known as one of the most loyal of new Labour MPs and was swiftly rewarded with promotion into the lower tiers of government. Not that he agreed with the leadership on everything, of course; it's just that he didn't like to advertise the fact. 'I'm not someone who has aired my differences with the party in public,' he says. 'I'm a football man. I do that in the changing room. On the pitch I tend to play the team game.'

In 2006, as Blair began the process of winding up his leadership of the party, Burnham's was one of the names he cited as the future of Labour, alongside those of Douglas Alexander, Ed Balls, David Miliband, Ed Miliband, James Purnell and Pat McFadden. Of those seven, four have now departed from the House of Commons, while another has already had his chance at leadership and blown it: the future isn't working out as planned.

By that stage, Burnham was making his way through the ranks, spending a while as a health minister, where he described his first week as one of mixed blessings: 'It's probably my worst nightmare to find out that my first parliamentary appearance would be winding up on a debate on deficits in the NHS,' he observed, though on a positive note: 'my week had begun on a high with Everton winning.' (He's rather partial to football, in case it had escaped anyone's attention.)

Following time spent in other jobs - Europe minister, chief secretary to the Treasury and culture secretary - he returned to the health department as secretary of state in 2009, and subsequently made the portfolio his own, serving as shadow health spokesperson during Ed Miliband's leadership.

In 2007 he called for the launch of an NHS constitution to spell out the institution's core values and 'to settle a new consensus around the NHS as the right model for Britain's healthcare needs for at least the medium term, if not for the longer term'.

He has also been campaigning for many years for the integration of health and care provision, proposing the creation of a National Health and Care Service. For a politician who claims to like 'doing things that are bold, important, setting a big agenda,' this has been his big idea. It hasn't, though, really sparked into life, and no one discusses its implications: what it means, how it would work. It's quite possibly a very policy indeed, but it sounds dull the way he tells it, and it hasn't caught the public imagination.

His bland, if not blind, loyalty in government led him into some more controversial areas. He was a keen advocate for the issuing of compulsory identity cards, he defended the PFI schemes for the building of new hospitals, and he suggested that the government might need to act to prevent alcohol being sold too cheaply. He was also called upon to implement the decision to scrap the plans for a so-called super-casino in Manchester, Gordon Brown's one distinctive repudiation of the Blair years.

And then there was the Stafford Hospital scandal. He set up the official enquiry into problems at Stafford immediately he became health secretary, but some still felt that there were outstanding questions, and that, in the words of The Spectator, 'he'll never be able to win a Labour leadership contest until he has a proper answer to those questions'.

Elsewhere, he has been dismissive of 'the educated, articulate, letter-writing people' who 'have no idea of what it is like to bring up a kid on a very low income and the pressure that creates and the difficulties that occur'. And he has been keen to stress the value of competitive sport: 'Competitiveness teaches good life values, winning and losing and taking in your stride, teamwork, discipline and a sense of obligation.'

In his time as secretary of state for culture, media and sport, he trumpeted his love of The Royle Family, professed himself - like Stella Creasy - to be a fan of the Wedding Present (particularly, and predictably, their 1987 album George Best), and claimed that 'Jeff Stelling epitomises standards in broadcasting'. He also mounted a robust defence of printed newspapers, arguing that that their 'heritage means something and can help people navigate a world where there is an ocean of shite on the internet'.

The great mystery about Burnham is why he's been talked up for so long and promoted so young. He gives the impression of being competent and personable, but largely uninspiring; an able lieutenant, perhaps, but no commander. He is the only leadership candidate this time who also went for the job in 2010. On that occasion, he finished fourth in a field of five, which was a little unkind - he was probably the third best option.

Above all, though, as he never ceases to remind us, he's a football fan. 'The Burnham family are a close-knit mob and there are three organisations that matter to us,' he once remarked: 'Everton Football Club, the Labour Party and the Catholic church - in that order.'

This is the first in a series of profiles of the four candidates in the Labour Party leadership election. Like the pieces I posted about the candidates for deputy leader, these are drawn entirely from the media, so they could be riddled with errors. Tomorrow: Liz Kendall

Back in 1993-94 the Observer used to run a feature called Any Questions, in which they told us who their interviewee would be next week and invited readers to send in their queries. And, as far as I can tell, this represented Andy Burnham's first appearances in the national press, with questions to Ian Botham, Graham Gooch and indeed to the ever fascinating Mary Whitehouse.

Sadly the names weren't attached to specific queries, so we'll never know whether Burnham was the one who asked Whitehouse about sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll. Probably not. Given his love of sport, he's more likely to have been the one who asked her: 'Do you regret not having had a professional tennis career?'

Born in 1970, Andy Burnham studied English at Cambridge University and followed what was rapidly becoming the conventional path into Labour Party politics: he worked as a researcher for Tessa Jowell and as parliamentary officer for the NHS confederation, before getting a nice job administering the Football Task Force that had been set up by Tony Banks, minister of sport in Tony Blair's first government.

The aims of the Task Force were to combat racism in football, to encourage disabled access, to help 'players to act as role models in terms of behaviour and sportsmanship', and to give fans a voice, particularly in terms of 'ticketing and pricing policies that reflect the need of all on an equitable basis'. As the new Premier League season gets into its stride, you can judge their successes for yourself.

The aims of the Task Force were to combat racism in football, to encourage disabled access, to help 'players to act as role models in terms of behaviour and sportsmanship', and to give fans a voice, particularly in terms of 'ticketing and pricing policies that reflect the need of all on an equitable basis'. As the new Premier League season gets into its stride, you can judge their successes for yourself.From there, it was but a short step to becoming a political adviser to Chris Smith, the culture secretary, and thence a safe seat in Leigh, though his parachuted arrival was not to the taste of everyone in the local party. 'This is jobs for the boys,' one member complained. 'It stinks to high heaven.'

Duly elected in 2001, he became known as one of the most loyal of new Labour MPs and was swiftly rewarded with promotion into the lower tiers of government. Not that he agreed with the leadership on everything, of course; it's just that he didn't like to advertise the fact. 'I'm not someone who has aired my differences with the party in public,' he says. 'I'm a football man. I do that in the changing room. On the pitch I tend to play the team game.'

In 2006, as Blair began the process of winding up his leadership of the party, Burnham's was one of the names he cited as the future of Labour, alongside those of Douglas Alexander, Ed Balls, David Miliband, Ed Miliband, James Purnell and Pat McFadden. Of those seven, four have now departed from the House of Commons, while another has already had his chance at leadership and blown it: the future isn't working out as planned.

By that stage, Burnham was making his way through the ranks, spending a while as a health minister, where he described his first week as one of mixed blessings: 'It's probably my worst nightmare to find out that my first parliamentary appearance would be winding up on a debate on deficits in the NHS,' he observed, though on a positive note: 'my week had begun on a high with Everton winning.' (He's rather partial to football, in case it had escaped anyone's attention.)

Following time spent in other jobs - Europe minister, chief secretary to the Treasury and culture secretary - he returned to the health department as secretary of state in 2009, and subsequently made the portfolio his own, serving as shadow health spokesperson during Ed Miliband's leadership.

In 2007 he called for the launch of an NHS constitution to spell out the institution's core values and 'to settle a new consensus around the NHS as the right model for Britain's healthcare needs for at least the medium term, if not for the longer term'.

He has also been campaigning for many years for the integration of health and care provision, proposing the creation of a National Health and Care Service. For a politician who claims to like 'doing things that are bold, important, setting a big agenda,' this has been his big idea. It hasn't, though, really sparked into life, and no one discusses its implications: what it means, how it would work. It's quite possibly a very policy indeed, but it sounds dull the way he tells it, and it hasn't caught the public imagination.

His bland, if not blind, loyalty in government led him into some more controversial areas. He was a keen advocate for the issuing of compulsory identity cards, he defended the PFI schemes for the building of new hospitals, and he suggested that the government might need to act to prevent alcohol being sold too cheaply. He was also called upon to implement the decision to scrap the plans for a so-called super-casino in Manchester, Gordon Brown's one distinctive repudiation of the Blair years.

And then there was the Stafford Hospital scandal. He set up the official enquiry into problems at Stafford immediately he became health secretary, but some still felt that there were outstanding questions, and that, in the words of The Spectator, 'he'll never be able to win a Labour leadership contest until he has a proper answer to those questions'.

Elsewhere, he has been dismissive of 'the educated, articulate, letter-writing people' who 'have no idea of what it is like to bring up a kid on a very low income and the pressure that creates and the difficulties that occur'. And he has been keen to stress the value of competitive sport: 'Competitiveness teaches good life values, winning and losing and taking in your stride, teamwork, discipline and a sense of obligation.'

In his time as secretary of state for culture, media and sport, he trumpeted his love of The Royle Family, professed himself - like Stella Creasy - to be a fan of the Wedding Present (particularly, and predictably, their 1987 album George Best), and claimed that 'Jeff Stelling epitomises standards in broadcasting'. He also mounted a robust defence of printed newspapers, arguing that that their 'heritage means something and can help people navigate a world where there is an ocean of shite on the internet'.

The great mystery about Burnham is why he's been talked up for so long and promoted so young. He gives the impression of being competent and personable, but largely uninspiring; an able lieutenant, perhaps, but no commander. He is the only leadership candidate this time who also went for the job in 2010. On that occasion, he finished fourth in a field of five, which was a little unkind - he was probably the third best option.

Above all, though, as he never ceases to remind us, he's a football fan. 'The Burnham family are a close-knit mob and there are three organisations that matter to us,' he once remarked: 'Everton Football Club, the Labour Party and the Catholic church - in that order.'

This is the first in a series of profiles of the four candidates in the Labour Party leadership election. Like the pieces I posted about the candidates for deputy leader, these are drawn entirely from the media, so they could be riddled with errors. Tomorrow: Liz Kendall

Sunday, 16 August 2015

A throw of the dice

Throughout this Labour leadership contest, I've been predicting a victory for Yvette Cooper. Indeed I was predicting it in April before the general election. I don't like to change my predictions, so I won't. Despite everything, Yvette Cooper will become the leader of the Labour Party.

I am aware, however, that this is - to put it mildly - a minority position. And that I have no evidence for it whatsoever.

In fact, if I'd been paying attention to myself, I would have concluded that Jeremy Corbyn, currently the red-hot favourite, was the likely winner. 'New political forces will emerge, whether within the existing parties or outside of them,' I wrote in 2012; 'things are about to change quite radically.' I added last year that UKIP weren't that change. But maybe Corbyn is the catalyst for this change.

So let's assume that that I'm as wrong now as I was when I placed money on Peter Hain succeeding Tony Blair, the issue is whether Corbyn will be any good as leader.

There are three basic tasks for the opposition. First, that they oppose government policies by producing alternatives. Second, that those alternatives change the terms of the debate. Third, that by changing the debate, there comes at least a reasonable chance of winning the next election.

The first is where things have really gone wrong for the Labour establishment. Losing the election was disastrous, but Harriet Harman's call for MPs to abstain on welfare reform added insult to injury. It smacked of democratic centralism, implying that since the Tories had won the election, then their policies had to be accepted. The decision to abstain made no difference whatsoever to the outcome of the vote, but Harman has been around long enough that she should have got the grasp of symbolic gestures by now. And yet she blew it, and no other single event has done as much to strengthen Corbyn's cause.

Frankly, Corbyn couldn't make a worse fist of opposition than Harman already has.

His MPs, however, could make it much, much worse. If a significant number of them effectively refuse to accept the party's vote, then he will fail from the outset. And they may well do so. They could quote Tony Benn at a meeting of the shadow cabinet in 1970: 'When the boat is sunk, you can't exactly rock it.'

Assuming, though, that he could assert his authority of the parliamentary party, could Corbyn re-frame the national debate? Yes. Is it likely? No. He would have the entire media against him; not just the usual suspects, but the whole of what some like to call the legacy media.

And maybe in there is the hope: that social media and the revival of public meetings can bypass the newspapers and the broadcasters. Maybe Facebook and The Trews will eclipse the Daily Mail and the Ten O'Clock News as the source of political information. I'm not convinced. Not in the short-term. So it would require an active mass membership - in real life, not on the internet - to counteract media hostility. Again I'm not convinced. Nor do I see any sign of Corbyn supporters seeking to persuade, rather than to assert.

Could he offer the possibility of an election win? Well, very probably not. But honestly, you never really know. Labour winning in 2020 is such an uphill task anyway. Someone on Twitter (I apologise for forgetting who - let me know it was you) suggested that, if this were a dice game, Labour needed to throw a six to win, and that Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall could only manage threes and fours. Corbyn, on the other hand, offered the chance of either a one or a six.

Maybe. It is possible that Corbyn (Corbyn, of all people!) could build a People's Army that would massively outnumber Nigel Farage's following, a crusade that stretches far beyond Parliament. How this works within the existing Labour Party structure, however, I have no idea.

I have a fear that a Corbyn-led Labour might echo the miners' strike of 1984-85. There sprang up then a national network of support groups that was really quite extraordinary. It was, said the Financial Times, 'the biggest and most continuous civilian mobilisation since the Second World War'.

If you were involved, even in a peripheral way, with this movement, it was almost impossible to credit the opinion polls which showed the majority of the public firmly on the side of the government and against the NUM. But that was the reality. Most people didn't support the miners, and the result was one of the left's most celebrated of heroic defeats.

Back before Corbyn declared himself a candidate, I wrote: 'The task of choosing a new leader is to find someone who can articulate a sense of hope for the future, to persuade somewhere around a quarter of the electorate that he or she can help us build a better society.'

At the moment, there's only one candidate who's being seen in those terms. But I suspect there's only one six on his die (if that) and that the other faces are all ones. And I fear that Labour might actually need a double-six anyway.

I have yet to decide who to vote for. Over the course of the next week, I shall look back over the careers of the four candidates as a way of clarifying that question for myself. And I shall start tomorrow with Andy Burnham.

I am aware, however, that this is - to put it mildly - a minority position. And that I have no evidence for it whatsoever.

In fact, if I'd been paying attention to myself, I would have concluded that Jeremy Corbyn, currently the red-hot favourite, was the likely winner. 'New political forces will emerge, whether within the existing parties or outside of them,' I wrote in 2012; 'things are about to change quite radically.' I added last year that UKIP weren't that change. But maybe Corbyn is the catalyst for this change.

So let's assume that that I'm as wrong now as I was when I placed money on Peter Hain succeeding Tony Blair, the issue is whether Corbyn will be any good as leader.

There are three basic tasks for the opposition. First, that they oppose government policies by producing alternatives. Second, that those alternatives change the terms of the debate. Third, that by changing the debate, there comes at least a reasonable chance of winning the next election.

The first is where things have really gone wrong for the Labour establishment. Losing the election was disastrous, but Harriet Harman's call for MPs to abstain on welfare reform added insult to injury. It smacked of democratic centralism, implying that since the Tories had won the election, then their policies had to be accepted. The decision to abstain made no difference whatsoever to the outcome of the vote, but Harman has been around long enough that she should have got the grasp of symbolic gestures by now. And yet she blew it, and no other single event has done as much to strengthen Corbyn's cause.

Frankly, Corbyn couldn't make a worse fist of opposition than Harman already has.

His MPs, however, could make it much, much worse. If a significant number of them effectively refuse to accept the party's vote, then he will fail from the outset. And they may well do so. They could quote Tony Benn at a meeting of the shadow cabinet in 1970: 'When the boat is sunk, you can't exactly rock it.'

Assuming, though, that he could assert his authority of the parliamentary party, could Corbyn re-frame the national debate? Yes. Is it likely? No. He would have the entire media against him; not just the usual suspects, but the whole of what some like to call the legacy media.

And maybe in there is the hope: that social media and the revival of public meetings can bypass the newspapers and the broadcasters. Maybe Facebook and The Trews will eclipse the Daily Mail and the Ten O'Clock News as the source of political information. I'm not convinced. Not in the short-term. So it would require an active mass membership - in real life, not on the internet - to counteract media hostility. Again I'm not convinced. Nor do I see any sign of Corbyn supporters seeking to persuade, rather than to assert.

Could he offer the possibility of an election win? Well, very probably not. But honestly, you never really know. Labour winning in 2020 is such an uphill task anyway. Someone on Twitter (I apologise for forgetting who - let me know it was you) suggested that, if this were a dice game, Labour needed to throw a six to win, and that Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall could only manage threes and fours. Corbyn, on the other hand, offered the chance of either a one or a six.

Maybe. It is possible that Corbyn (Corbyn, of all people!) could build a People's Army that would massively outnumber Nigel Farage's following, a crusade that stretches far beyond Parliament. How this works within the existing Labour Party structure, however, I have no idea.

I have a fear that a Corbyn-led Labour might echo the miners' strike of 1984-85. There sprang up then a national network of support groups that was really quite extraordinary. It was, said the Financial Times, 'the biggest and most continuous civilian mobilisation since the Second World War'.

If you were involved, even in a peripheral way, with this movement, it was almost impossible to credit the opinion polls which showed the majority of the public firmly on the side of the government and against the NUM. But that was the reality. Most people didn't support the miners, and the result was one of the left's most celebrated of heroic defeats.

Back before Corbyn declared himself a candidate, I wrote: 'The task of choosing a new leader is to find someone who can articulate a sense of hope for the future, to persuade somewhere around a quarter of the electorate that he or she can help us build a better society.'

At the moment, there's only one candidate who's being seen in those terms. But I suspect there's only one six on his die (if that) and that the other faces are all ones. And I fear that Labour might actually need a double-six anyway.

I have yet to decide who to vote for. Over the course of the next week, I shall look back over the careers of the four candidates as a way of clarifying that question for myself. And I shall start tomorrow with Andy Burnham.

Saturday, 15 August 2015

The Labour deputy leadership

Where do we stand in the Labour Party deputy leadership election? Having spent some time wandering through the newspapers and around the internet, looking at the careers of the candidates, I now have to decide who to vote for.

These are the runners, pictured from left to right: Caroline Flint (age 53), Angela Eagle (54), Ben Bradshaw (54), Tom Watson (48) and Stella Creasy (38).

So what can we say about these five? Well, first, that they don't actually make for a bad field, and second, that they do have a great deal in common.

In particular, they're all unashamedly professional politicians, with only Bradshaw's previous incarnation as a radio reporter departing from the normal career path. (And that wasn't straying too far: the separation between media and politics was barely discernible in the 1990s.) Their time in Parliament has mostly been characterised by loyalty, though Watson and Flint did separately resign from government, seemingly in would-be coups aimed against, respectively, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. And all are, insofar as such distinctions mean anything any more, on what would have been see as the right of the party in the 1980s. At least, though, they were all educated at different universities.

Given that the deputy leadership position is not of the greatest significance - Denis Healey once said it was worth only 'a pitcherful of warm spit' - perhaps one shouldn't spend too long deliberating. Apart from anything else, it's hard to see the final choice really attracting much attention, given the Jeremy Corbyn story that'll be breaking one way or another at the same time.

But still, it does matter. At the very least, it 'sends a signal', as politicians like to say. And in the context of the Corbyn story, the signal might actually mean a little more than usual this time.

A victory for Bradshaw or Flint would indicate that the smooth operators are still with us. And I don't think that's where the Labour Party should be heading. They're the kind of politicians who remind me of a great line in one of Hugh Trevor-Roper's letters: 'In general, actors have no minds, only memories and poses.'

Elsewhere, I struggle to see Watson as anything other than a burly bruiser with authoritarian tendencies. Again, he seems to me to represent a politics that Labour should be leaving behind.

But both Eagle and Creasy are good, strong candidates. Electing either one would send a strong signal that Labour is a serious, radical party.

Judging entirely by media coverage (which is all I have), I'm impressed by Eagle's consistency, commitment and decency. I know she studied PPE at Oxford, and Lord knows we've had more than enough of them in recent times, but sometimes we have to overlook youthful mistakes. More importantly, she's retained an unusual degree of individuality for someone who navigated the New Labour years more or less successfully. Maybe it's the early role models standing her in good stead; when asked her favourite book, she rather splendidly nominated Mae West's autobiography Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It.

It's hard to resist that, and I hope Eagle gets a very senior position in the new shadow cabinet. But as my first choice for deputy leader, I think I've concluded that Stella Creasy is the better option, for the following reason.

One of the great myths peddled by Blair was that the Labour Party could achieve nothing unless it were in government. He was wrong. And since the Labour Party has spent most of its existence in opposition, and there's a good chance that the next decade will add to that record, it's important to recognise that he was wrong.

At its best, the Labour Party has been able to transform people's lives at the grassroots, even when it hasn't occupied Downing Street. It was built on a sense of mutuality and community self-help, the sense that, in Harold Wilson's words: 'The Labour Party is a moral crusade or it is nothing.' Many of the old traditions have died, of course, victims of affluence and neglect. But if the party is to have any hope of rebuilding, it needs to do so from the ground up, rediscovering the fact that power is not the preserve of Westminster.

Creasy seems to me to be the one who sees that most clearly, and has thought most carefully about the future. And, talking of signals, I like the fact that she is one of only twenty-four Labour and Co-operative MPs, having been endorsed by both parties.

She is, of course, absurdly young, and has little experience of life or parliament and none whatsoever of government. But she does at least look as though she's ready for the long haul, and will still be there on the other side.

These are the runners, pictured from left to right: Caroline Flint (age 53), Angela Eagle (54), Ben Bradshaw (54), Tom Watson (48) and Stella Creasy (38).

So what can we say about these five? Well, first, that they don't actually make for a bad field, and second, that they do have a great deal in common.

In particular, they're all unashamedly professional politicians, with only Bradshaw's previous incarnation as a radio reporter departing from the normal career path. (And that wasn't straying too far: the separation between media and politics was barely discernible in the 1990s.) Their time in Parliament has mostly been characterised by loyalty, though Watson and Flint did separately resign from government, seemingly in would-be coups aimed against, respectively, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. And all are, insofar as such distinctions mean anything any more, on what would have been see as the right of the party in the 1980s. At least, though, they were all educated at different universities.

Given that the deputy leadership position is not of the greatest significance - Denis Healey once said it was worth only 'a pitcherful of warm spit' - perhaps one shouldn't spend too long deliberating. Apart from anything else, it's hard to see the final choice really attracting much attention, given the Jeremy Corbyn story that'll be breaking one way or another at the same time.

But still, it does matter. At the very least, it 'sends a signal', as politicians like to say. And in the context of the Corbyn story, the signal might actually mean a little more than usual this time.

A victory for Bradshaw or Flint would indicate that the smooth operators are still with us. And I don't think that's where the Labour Party should be heading. They're the kind of politicians who remind me of a great line in one of Hugh Trevor-Roper's letters: 'In general, actors have no minds, only memories and poses.'

Elsewhere, I struggle to see Watson as anything other than a burly bruiser with authoritarian tendencies. Again, he seems to me to represent a politics that Labour should be leaving behind.

But both Eagle and Creasy are good, strong candidates. Electing either one would send a strong signal that Labour is a serious, radical party.

Judging entirely by media coverage (which is all I have), I'm impressed by Eagle's consistency, commitment and decency. I know she studied PPE at Oxford, and Lord knows we've had more than enough of them in recent times, but sometimes we have to overlook youthful mistakes. More importantly, she's retained an unusual degree of individuality for someone who navigated the New Labour years more or less successfully. Maybe it's the early role models standing her in good stead; when asked her favourite book, she rather splendidly nominated Mae West's autobiography Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It.

It's hard to resist that, and I hope Eagle gets a very senior position in the new shadow cabinet. But as my first choice for deputy leader, I think I've concluded that Stella Creasy is the better option, for the following reason.

One of the great myths peddled by Blair was that the Labour Party could achieve nothing unless it were in government. He was wrong. And since the Labour Party has spent most of its existence in opposition, and there's a good chance that the next decade will add to that record, it's important to recognise that he was wrong.

At its best, the Labour Party has been able to transform people's lives at the grassroots, even when it hasn't occupied Downing Street. It was built on a sense of mutuality and community self-help, the sense that, in Harold Wilson's words: 'The Labour Party is a moral crusade or it is nothing.' Many of the old traditions have died, of course, victims of affluence and neglect. But if the party is to have any hope of rebuilding, it needs to do so from the ground up, rediscovering the fact that power is not the preserve of Westminster.

Creasy seems to me to be the one who sees that most clearly, and has thought most carefully about the future. And, talking of signals, I like the fact that she is one of only twenty-four Labour and Co-operative MPs, having been endorsed by both parties.

She is, of course, absurdly young, and has little experience of life or parliament and none whatsoever of government. But she does at least look as though she's ready for the long haul, and will still be there on the other side.

This concludes my look at the deputy leadership candidates. Next week I shall go through the leadership hopefuls to try to work out who to vote for in that election.

Wednesday, 12 August 2015

One of the disappointed: a portrait of Angela Eagle

PLEASE NOTE: A fuller and much better version of this can be found here on the Lion & Unicorn site, where I now post.

I've long thought that one of the most clear-cut illustrations of Britain's lack of democracy was the case of Lynda Chalker. She was the minister for overseas development in John Major's government until she lost her seat as MP for Wallasey in the 1992 general election. At which point, she was promptly given a peerage, so that she could continue in the same job, where she remained until the government fell in 1997.

Just to be clear: Chalker was a perfectly competent minister. But really, what's the point in democracy if you can't actually vote someone out of office?

But this isn't about Chalker. The important figure here is the Labour Party candidate who took Wallasey in that 1992 election.

Born in 1961, Angela Eagle studied PPE at Oxford, after which she worked first for the CBI and then COHSE (a health service union, now part of Unison). Whilst in the latter post, she co-authored a Fabian Society pamphlet which called for all-women shortlists when selecting candidates for safe Labour seats.

Her own selection for Wallasey was not dependent on such an arrangement, though it did attract some controversy. The existing Labour candidate was Lol Duffy, a shop steward in Birkenhead who'd come within 300 votes of winning in 1987. But he was deemed to be a supporter of the Trotskyist group Socialist Organiser, so the National Executive Committee intervened and deselected him for the 1992 election.

Seizing the opportunity, Eagle navigated the ensuing selection process with ease, beating into second place Mike Groves, a former member of Liverpool folk group the Spinners. (If you don't remember them, you're too young to have watched light entertainment television in the 1970s.) On a swing that matched the national average, she then took the seat from Chalker and entered Parliament at the age of thirty-one as, in the words of the Guardian, 'a potential bright youngish Labour thing'.

In the ensuing Labour leadership election she nominated Bryan Gould, against the winning candidate John Smith, though she was critical of the expense and length of the contest. 'If we carry on like this,' she argued, 'we will become the party of the perpetual ballot, frantically spending our time and money organising elections for everything under the sun. We will have no money left to campaign except in our own internal elections. And the Tories, who have no internal democracy, will laugh all the way to Downing Street.'

Eagle served her parliamentary apprenticeship during the slow-motion suicide of John Major's government. She attracted some attention for her fierce attacks on the likes of Cedric Brown, the 'fat cat' head of British Gas, and Neil Hamilton, the Tory MP who came to epitomize sleaze, but still found time to vote in support of a deeply controversial pay rise for MPs in 1996.

Early on she attracted the attention of Tony Blair and, following the Labour landslide of 1997, she became a junior minister, at thirty-six the youngest member of his government. By the time the party left office thirteen years later, she had risen to become pensions minister under Gordon Brown.

In public perception, however, her political career counted for very little. Much more interesting were her inclusion in the Commons cricket team (a former member of the Lancashire Schoolgirls XI, she was said to be a useful bowler), and the fact that her twin sister, Maria, was also elected to Parliament in 1997.

Even better was the interview she gave later that year to the Independent, in which she announced that she was in 'a long-term and very happy relationship' with a woman. As reported in the Daily Express, and elsewhere, this made her 'the first woman politician to publicly admit she is gay'.

She wasn't - that would have been Maureen Colquhoun, the Labour MP for Northampton North, back in the 1970s - but even so, it was a big deal at a time when there were vanishingly few lesbians in public life. But this was the late 1990s and the tide was turning. 'Attitudes have changed,' Eagle said. 'I think people are a lot more sensible than we sometimes give them credit for.'

Coming out was a ground-breaking move that saw her receive a message of support from, inter alia, Chrissie Hynde, a note she later cited as her most treasured possession (she's a big Pretenders fan). It also saw her ranked #7 in the Independent on Sunday's list of Women of the Year, two places behind Ann Widdecombe, and only one place behind Dolly the Sheep.

Little since then has excited the same level of media interest. Which is unfortunate, because Eagle was no New Labour robot. She was critical of the mishandling of Ken Livingstone's bid to be the London mayoral candidate in 1999, she heckled Blair when he was explaining to the Commons why we needed to invade Iraq, and in 2003 she co-founded the New Wave Labour group, arguing that the party was on the wrong political track. 'The third way has failed to present any genuine alternative,' she said, pointing out that markets make 'good servants, but poor masters.'