I quote from that speech, because it's both characteristic and unusual. Unusual because it's rare to hear him indulge in coarse language in public; but characteristic because he never was much of a phrase-maker. 'Fuck the rich' is as pithy as he's ever got, and it's not a startlingly original phrase.

Jeremy Corbyn differs a little from the previous eight candidates who I've written about over the last fortnight - though not entirely, since he's similarly done nothing but politics from an early age. He is, however, considerably older (born in 1949) and he doesn't have a degree: he went to the North London Polytechnic to do trade union studies, but left before completing the course. Instead he did a couple of years voluntary work in Jamaica and returned to become an official with the National Union of Tailors and Garment Makers (quite a big union at its peak, but long since merged into the GMB).

There was some surprise, incidentally, when Corbyn revealed at a hustings last month that he'd never smoked cannabis. But it was typical of the left of his generation: there was an austerity that verged on the puritanical. He may have been at a poly in the 1960s, but that didn't mean he was to be confused with a load of bourgeois hippies.

He was elected to Haringey council in North London in 1974 and stayed there till he entered Parliament in 1983 as the MP for Islington North. In that election, he beat not only the Tory and SDP candidates, but also the former Labour MP, Michael O'Halloran, standing as Independent Labour.

Even before he arrived in Westminster, Corbyn was well known in Labour politics, described in The Times as 'the veteran left-wing campaigner for squatters' rights'. The paper further pointed out that he'd be difficult to expel from the party: 'Mr Corbyn, like Mr Livingstone, is no "entryist". He has been a Labour Party member since his youth.'

The early 1980s were exciting times for the left in London, for while the party was floundering nationally, it was making substantial headway in the capital. And Corbyn was a key part of that. He was never the front man, but he was the kind of figure that anyone who encountered the left at the time would recognise: the man who worked indefatigably in the back office, emerging only to sit through interminable meetings, the one whose corduroy trousers bore telltale signs of Gestetner ink from hours of duplicating newsletters.

His greatest contribution to the cause was running London Labour Briefing, the journal that effectively coordinated the left's capture of the capital in the 1980s. Unusually for a socialist publication of the era, Briefing concerned itself with tactics not ideology, and concentrated on local government, where the resistance to Margaret Thatcher's government was at its most effective. It was a clearinghouse for information, not a theoretical journal. Ken Livingstone's coup against Andrew McIntosh to take control of the GLC in 1981 was plotted in the pages of Briefing.

The same year the journal published an article by Peter Tatchell, arguing: 'We must look to new, more militant forms of extra-parliamentary opposition which involve mass popular participation and challenge the government's right to rule.' And it was Michael Foot's hysterical response to that article that turned Tatchell briefly into the tabloids' favourite leftie villain.

The Tatchell episode ended in farce and failure, but mostly Briefing was an impressively successful enterprise. The politics of diversity that it championed were denounced at the time as loony left, but they seeped into alternative culture and have since taken over the mainstream.

Corbyn went on every demonstration, and he normally spoke, but he was no orator like Tony Benn. He supported every strike, but he was no firebrand like Arthur Scargill. He attended every meeting, but he was no thinker or innovator like Ken Livingstone. In short, he was one of nature's corporals. And he was very good at it. The fact that he currently has the best organised campaign of any of the leadership candidates should come as no surprise at all: it's what he does - those rallies don't organise themselves, you know.

In Parliament, he was a keen defender of the Bennite principles enshrined in the 1983 manifesto, but it was immediately obvious that the party, under the leadership of Neil Kinnock, was moving in another direction, particularly after the defeat of the miners' strike and Kinnock's conference speech denouncing Militant.

'What is clear,' observed Corbyn in 1988, 'is that the Labour Party decided a long time ago, in 1985, that the official party policy was a vote-loser and that something had to be done about it.'

He and the rest of the left were increasingly isolated under Kinnock, then under John Smith and most notably under Tony Blair. Throughout, Corbyn could be found voting according to his conscience rather than following the whip.

He and the rest of the left were increasingly isolated under Kinnock, then under John Smith and most notably under Tony Blair. Throughout, Corbyn could be found voting according to his conscience rather than following the whip.When he got reported - which was seldom, for the media found nothing of interest in him - he tended to be speaking against party policy. 'Most people are not opposed to raising the top level of tax,' he said just before the 1997 election, even as Gordon Brown promised no income tax rises. 'And those who made lots of money under Thatcher should pay more.'

He was also attracted, and lent his weight, to any cause that seemed to be opposed to the British, American or Israeli states. This led him, and much of the left, into some very dubious company.

It also allowed some notable omissions. There's a revealing entry in one of Tony Benn's diaries in 1989 when he goes on a protest against the massacre of students in Tiananmen Square, and notes: 'It was the first time I had ever spoken in public against a communist government.' You have to say that he left it a bit late; this was only five months before the German people began to dismantle the Berlin Wall.

Corbyn's associations with groups like Sinn Fein/IRA and Hamas will undoubtedly come back to haunt him, should he be elected leader. And I don't think there's any mileage in the leftist argument that it's all about trying to find peaceful ways forward, because it's not true: the motivation was and is political, not humanitarian.

In the run-up to the 1992 election, Conservative Central Office commissioned an analysis of Labour MPs and their expressed support for 'extremist views'. It concluded that in joint first place were Bill Michie and Bob Parry, but Corbyn came in an honourable third place, level pegging with Harry Cohen and Dennis Skinner, and just ahead of Tony Banks, Eddie Loyden and Max Madden, followed by a further group of Harry Barnes, Tony Benn and Alice Mahon. (Congratulations, by the way, if you recognise all those names - you'll do well if they ever introduce a politics spin-off from Pointless.)

As the reforms of the Kinnock years became embedded, he warned that the abandonment of ideology was damaging Labour's membership. This is him in 1990:

People are not coming into the party, fewer people are coming to meetings, and there is a very low level of public activity in general. The party has not got a healthy base. It is all very shallow. We do our opinion polls, find out what people want and say, 'Okay, you can have it,' without asking what kind of society we have now, and what kind of society we want to replace it.Just to make the point again that Corbyn was no inspiration as a wordsmith, compare this with Austin Mitchell's rather more striking formulation the previous year, saying that Labour had become: 'a mass party without members, an ideological crusade without an agreed ideology, a people's party cut off from the people.'

But Corbyn worked hard. And that work is reflected in his current standing. A lot of people have a great deal of respect for him, in trade unions and campaigning groups around the country, and particularly in London. There are also tens of thousands who marched with him on demonstrations over the years but who didn't stay the pace, and gave up on political activism, burnt out and disillusioned; many of these have returned to Labour in the last few weeks.

He is not the leader that anyone would have chosen. But, as I've discussed here before, he was the last man standing when the left decided it should try to field a candidate in the contest, in the seemingly absurd hope of having a say on the future direction of the party. And once he got up and running, it turned out that he had more support than anyone had imagined.

His effect on the campaign has been transformative, changing entirely the terms of the debate. And it has been for the better. This discussion - essentially over the legacy of New Labour - needed to be had, however painful and disagreeable it is. When he was leader, Ed Miliband was praised for keeping the party together, but it seems that he just delayed things for five years.

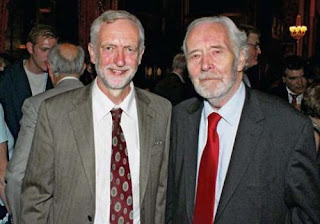

Corbyn himself has improved over these weeks. He's still no great speaker, but he looks like he's relaxing a little and consequently communicating better. He's developing some ability at handling the media that has never been apparent before. (Perhaps he's been getting tips off Ken Livingstone or Diane Abbott.)

Most importantly, he's found a winning formula, offering socialist authenticity as the man who never compromised his beliefs, but also indulging in terminology so vague that it might be mistaken for the theme song to Neighbours. Socialism, he says, is simple: 'You care for each other, you care for everybody, and everybody cares for everybody else. It's obvious, isn't it?'

Obvious perhaps, but still it's quite a long way from 'Fuck the rich'. Maybe the man's mellowing with age.

At the time of writing, Jeremy Corbyn is the clear favourite to be elected leader of the Labour Party next month. And that sentence represents, I think, the single most extraordinary political fact that I have ever recorded.

And that concludes my round-up of the four candidates for the Labour Party leadership, drawn - as ever - from newspaper reports. Tomorrow I shall stop procrastinating and decide who I should vote for.

* Additional note: After the 'fuck the rich' speech was repeated in Newsweek, following this post, a message was tweeted by the TimesArchive Twitter account: