What a buffoon I am! All these weeks and months I've been saying that Jeremy Corbyn wouldn't be elected leader of the Labour Party. And now he has been. I was wrong, completely and hopelessly wrong.

In my defence, I did from the outset say that Corbyn should be taken seriously, that he wasn't a joke candidate. But it was my conviction was that when it actually came to the crunch, the party would decide that the example of Iain Duncan Smith was not one that it wished to follow. And I was wrong. As I so often am.

But, despite my poor track record on predictions, I can at least confidently predict that it's going to be entertaining. God bless the party and all who sail in her.

Showing posts with label Iain Duncan Smith. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Iain Duncan Smith. Show all posts

Saturday, 12 September 2015

Monday, 31 August 2015

Debagging

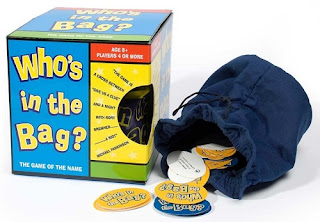

One of the things I write is a game called Who's in the Bag?, which is a simple - but effective - little thing. There's a bag full of cards, on each of which there are three names and, without actually speaking the names themselves, you have to get your team-mates to guess who they are. There's a timer as well. It sells well and has done for a couple of decades now.

Every few years, though, it has to be updated to allow for changing tastes and fashions. Some people - say, Winston Churchill, Jane Austen, Stevie Wonder - are likely to stay in every edition. But others pass their sell-by date and have to be dropped. Robert Kilroy-Silk, for instance: he was thrown out of the Bag some time ago. Liam Gallagher more recently. For other reasons, Max Clifford and Rolf Harris won't be in the Bag this time. And meanwhile some new people will have emerged since the last version, who need to be added.

I'm now working on a new edition of both the main game and the add-on pack of cards. Which means I have to come up with over 1,200 names that I can reasonably expect to be recognised, or that are possible to guess even if they're not recognisable. Donald Trump, for example, is an easy name to convey, even if you've never heard of him. (Lucky you.) Similarly, Mary Beard, Nicola Sturgeon and Paddy Power.

The other factor is that this will probably still be in print in 2020. So there's an element of prediction here. Will Ed Sheeran still be a thing in five years time, or will he have faded in the same way as - oh, I don't know - Jake Bugg seems to have done? What about Harry Kane? Jennifer Lawrence? Will Katie Hopkins become big enough to warrant being put in the Bag?

It's a bit like a low-budget version of Madame Tussaud's selection process. I mentioned in my book A Classless Society that we knew Iain Duncan Smith was doomed as Tory leader when Tussaud's said he wouldn't get an effigy. 'He is not in the papers very much and you never hear his name,' said a spokesperson. 'We are not sure if our visitors will recognise him.' It was a damning verdict.

And the question that's currently troubling me is the parallel case of the Labour leadership. Whoever wins gets put in the Bag, of course. But the losers? If Andy Burnham doesn't get to be leader, is he going to become a household name? How about Jeremy Corbyn? Flavour of the month now, but if he fails to win this election, how big will his public profile be in a couple of years? Politicians generally aren't instantly familiar, as Pointless discovered a couple of years ago.

Much safer is the process of discarding people. Amongst those who I've thrown out of the Bag this time are Ed Balls, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, Rebekah Brooks, Nick Clegg, Abu Hamza, Harriet Harman, Martin McGuinness, Peter Mandelson and Ian Paisley. These are, in my estimation, yesterday's men and women. There's a dangerous sense of power that comes with writing this game...

Any suggestions for people who have become famous in the last three years would be most appreciated.

Every few years, though, it has to be updated to allow for changing tastes and fashions. Some people - say, Winston Churchill, Jane Austen, Stevie Wonder - are likely to stay in every edition. But others pass their sell-by date and have to be dropped. Robert Kilroy-Silk, for instance: he was thrown out of the Bag some time ago. Liam Gallagher more recently. For other reasons, Max Clifford and Rolf Harris won't be in the Bag this time. And meanwhile some new people will have emerged since the last version, who need to be added.

I'm now working on a new edition of both the main game and the add-on pack of cards. Which means I have to come up with over 1,200 names that I can reasonably expect to be recognised, or that are possible to guess even if they're not recognisable. Donald Trump, for example, is an easy name to convey, even if you've never heard of him. (Lucky you.) Similarly, Mary Beard, Nicola Sturgeon and Paddy Power.

The other factor is that this will probably still be in print in 2020. So there's an element of prediction here. Will Ed Sheeran still be a thing in five years time, or will he have faded in the same way as - oh, I don't know - Jake Bugg seems to have done? What about Harry Kane? Jennifer Lawrence? Will Katie Hopkins become big enough to warrant being put in the Bag?

It's a bit like a low-budget version of Madame Tussaud's selection process. I mentioned in my book A Classless Society that we knew Iain Duncan Smith was doomed as Tory leader when Tussaud's said he wouldn't get an effigy. 'He is not in the papers very much and you never hear his name,' said a spokesperson. 'We are not sure if our visitors will recognise him.' It was a damning verdict.

And the question that's currently troubling me is the parallel case of the Labour leadership. Whoever wins gets put in the Bag, of course. But the losers? If Andy Burnham doesn't get to be leader, is he going to become a household name? How about Jeremy Corbyn? Flavour of the month now, but if he fails to win this election, how big will his public profile be in a couple of years? Politicians generally aren't instantly familiar, as Pointless discovered a couple of years ago.

Much safer is the process of discarding people. Amongst those who I've thrown out of the Bag this time are Ed Balls, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, Rebekah Brooks, Nick Clegg, Abu Hamza, Harriet Harman, Martin McGuinness, Peter Mandelson and Ian Paisley. These are, in my estimation, yesterday's men and women. There's a dangerous sense of power that comes with writing this game...

Any suggestions for people who have become famous in the last three years would be most appreciated.

Monday, 20 July 2015

Why don't you do it again?

Following Labour's massive defeat in the 1983 general election, the party began the long, painful march back to electoral success. A new leader, Neil Kinnock, was elected, senior figures stepped back from the front-line, and policies associated with the 1983 manifesto began gradually to be dropped.

And, just fourteen years later, the Conservative Party was finally removed from government.

The election defeats in 2010 and this year are not on the scale of 1983. Not quite. But there are, I think, echoes of the 1980s to be heard. In particular, there is an attitude within Labour that harks back to that long period of opposition.

In my book Rejoice! Rejoice! (available in paperback from all good retailers), I argued that the radicalism of Margaret Thatcher 'threw the left on the defensive, so that the Labour Party seemed constantly to be fighting rearguard actions, seeking to protect a status quo from which support was fast draining away.'

Every change made by the government, I said, was 'opposed until it had been implemented and had been seen to win popular approval, at which stage Labour accepted it. The impression given was that the party was hidebound and dogmatic, and yet paradoxically lacking in principle.'

And that, I fear, has been the impression that the party has again given in recent years. Because, under David Cameron, the Conservatives have rediscovered a Thatcherite zeal for reform, and Labour still hasn't worked out how to respond.

Those on the left often cite the achievements of Clement Attlee's government, the great changes that were wrought even at a time when the nation was in massive debt and struggling to cope with the aftermath of the Second World War. Against all the odds, and against conventional political wisdom, a new world was built. 'We were, as Winston Churchill said, a bankrupt nation,' reflected Nye Bevan, 'but nonetheless we did these things.'

The same may one day be said of Cameron's governments. In the face of a huge economic recession, the coalition set about the radical restructuring of the NHS, of education and of the benefits system. And Labour's reaction has been, as in the 1980s, simply to oppose every change that is mooted, to denounce it as unnecessary, vindictive and wrong, possibly evil. After which, the truth is gradually acknowledged - too late to be of any use - that maybe change was necessary after all.

Put another way: If a Labour government were to be elected in 2020, how many of the Tory reforms to education and welfare would it actually reverse? Precisely.

As acting leader, Harriet Harman (elected to Parliament in 1982) has at least tried another tack: of accepting large swathes of the government's benefits agenda as soon it was announced. Inevitably this has caused some tension in the party, with both the front-runners for the leadership - Yvette Cooper and Andy Burnham - distancing themselves from her approach.

They're probably right to do so. Apart from any question of morality and principle that Labour might wish to articulate, this isn't normally a successful political course to steer. When in opposition, the cry of 'me too' does not tend to get heard, no matter how loud you shout. This is particularly the case in the immediate aftermath of an election defeat, when no one is listening.

But there is an alternative. It starts by recognising that change is necessary, that there are no sacred cows and that things are going wrong. Which can be controversial, but shouldn't be.

To suggest that the NHS is failing to deliver the service that it should deliver is not the same as demanding that we abandon the institution entirely. It's merely to point to an obvious, if not often articulated, truth: the NHS isn't good enough. It really isn't. Its efficiency and patient care could be considerably improved, and the public has a right to expect better.

And the same is true elsewhere. Educational standards in the state sector are not high enough, and the public has a right to want improvement in the performance of Britain's schools. The benefit system has developed too many flaws to be allowed to continue unchallenged, and the public has a right to feel that its tax contributions could be better targeted.

When William Beveridge and the other great reformers of the 1940s set out to change society, they identified the five giant evils as squalor, ignorance, want, idleness and disease. Progress has been made, but you'd be hard pushed to claim that these giants have been slain.

Reform is necessary and inevitable. But by simply adopting a defensive position, Labour has - in the post-Attlee years - chosen not to participate in shaping that reform.

There have been exceptions, of course. There was James Callaghan as prime minister, for example, launching his great education debate in the 1970s, though it was a subsequent Tory government that actually made all the running, culminating in the Education Reform Act of 1988. Better yet, there was Frank Field, with his thinking-the-unthinkable transformation of the welfare state, which Gordon Brown point-blank refused to fund.

That latter case illustrates Labour's problem. If the entire system of benefits needed to be re-examined - and it did and does - then it's important to have the Labour Party coming up with some ideas. Because if it doesn't do so, then it simply hands over the whole thing to the Tories to make whatever changes they deem necessary. And the Conservatives may not have the same priorities. Which leaves Labour bleating on about Iain Duncan Smith's 'hated bedroom tax'.

The problem with not accepting the need for change - and therefore failing to initiate new thinking - is that it passes the agenda to your opponents. And it can take an awfully long time to recover from that.

I don't know if you remember Ed Miliband's speech to the 2011 Labour conference. Possibly not, though it was said to be enormously significant at the time: 'the most radical analysis of Britain's plight offered by any Labour leader since 1945,' according to the post-match punditry of Patrick Wintour in the Guardian. It was the speech that was going to reframe the public debate of capitalism, with its distinction between predators and producers.

But perhaps the most striking section of that speech was when Miliband dwelt on the past. There had been speculation that he was going to apologise for the mistakes made by the last Labour government. But he had much older fish to fry. 'Some of what happened in the 1980s was right,' he told conference. 'It was right to let people buy their council houses. It was right to cut taxes of 60, 70, 80 per cent. And it was right to change the rules on the closed shop, on strikes before ballots.'

Thirty years on, and Labour was still trying to get over its failed strategy in the 1980s. Before straightening its tie and going out to make the same mistakes all over again.

And, just fourteen years later, the Conservative Party was finally removed from government.

The election defeats in 2010 and this year are not on the scale of 1983. Not quite. But there are, I think, echoes of the 1980s to be heard. In particular, there is an attitude within Labour that harks back to that long period of opposition.

In my book Rejoice! Rejoice! (available in paperback from all good retailers), I argued that the radicalism of Margaret Thatcher 'threw the left on the defensive, so that the Labour Party seemed constantly to be fighting rearguard actions, seeking to protect a status quo from which support was fast draining away.'

Every change made by the government, I said, was 'opposed until it had been implemented and had been seen to win popular approval, at which stage Labour accepted it. The impression given was that the party was hidebound and dogmatic, and yet paradoxically lacking in principle.'

And that, I fear, has been the impression that the party has again given in recent years. Because, under David Cameron, the Conservatives have rediscovered a Thatcherite zeal for reform, and Labour still hasn't worked out how to respond.

Those on the left often cite the achievements of Clement Attlee's government, the great changes that were wrought even at a time when the nation was in massive debt and struggling to cope with the aftermath of the Second World War. Against all the odds, and against conventional political wisdom, a new world was built. 'We were, as Winston Churchill said, a bankrupt nation,' reflected Nye Bevan, 'but nonetheless we did these things.'

The same may one day be said of Cameron's governments. In the face of a huge economic recession, the coalition set about the radical restructuring of the NHS, of education and of the benefits system. And Labour's reaction has been, as in the 1980s, simply to oppose every change that is mooted, to denounce it as unnecessary, vindictive and wrong, possibly evil. After which, the truth is gradually acknowledged - too late to be of any use - that maybe change was necessary after all.

Put another way: If a Labour government were to be elected in 2020, how many of the Tory reforms to education and welfare would it actually reverse? Precisely.

As acting leader, Harriet Harman (elected to Parliament in 1982) has at least tried another tack: of accepting large swathes of the government's benefits agenda as soon it was announced. Inevitably this has caused some tension in the party, with both the front-runners for the leadership - Yvette Cooper and Andy Burnham - distancing themselves from her approach.

They're probably right to do so. Apart from any question of morality and principle that Labour might wish to articulate, this isn't normally a successful political course to steer. When in opposition, the cry of 'me too' does not tend to get heard, no matter how loud you shout. This is particularly the case in the immediate aftermath of an election defeat, when no one is listening.

But there is an alternative. It starts by recognising that change is necessary, that there are no sacred cows and that things are going wrong. Which can be controversial, but shouldn't be.

To suggest that the NHS is failing to deliver the service that it should deliver is not the same as demanding that we abandon the institution entirely. It's merely to point to an obvious, if not often articulated, truth: the NHS isn't good enough. It really isn't. Its efficiency and patient care could be considerably improved, and the public has a right to expect better.

And the same is true elsewhere. Educational standards in the state sector are not high enough, and the public has a right to want improvement in the performance of Britain's schools. The benefit system has developed too many flaws to be allowed to continue unchallenged, and the public has a right to feel that its tax contributions could be better targeted.

When William Beveridge and the other great reformers of the 1940s set out to change society, they identified the five giant evils as squalor, ignorance, want, idleness and disease. Progress has been made, but you'd be hard pushed to claim that these giants have been slain.

Reform is necessary and inevitable. But by simply adopting a defensive position, Labour has - in the post-Attlee years - chosen not to participate in shaping that reform.

There have been exceptions, of course. There was James Callaghan as prime minister, for example, launching his great education debate in the 1970s, though it was a subsequent Tory government that actually made all the running, culminating in the Education Reform Act of 1988. Better yet, there was Frank Field, with his thinking-the-unthinkable transformation of the welfare state, which Gordon Brown point-blank refused to fund.

That latter case illustrates Labour's problem. If the entire system of benefits needed to be re-examined - and it did and does - then it's important to have the Labour Party coming up with some ideas. Because if it doesn't do so, then it simply hands over the whole thing to the Tories to make whatever changes they deem necessary. And the Conservatives may not have the same priorities. Which leaves Labour bleating on about Iain Duncan Smith's 'hated bedroom tax'.

The problem with not accepting the need for change - and therefore failing to initiate new thinking - is that it passes the agenda to your opponents. And it can take an awfully long time to recover from that.

I don't know if you remember Ed Miliband's speech to the 2011 Labour conference. Possibly not, though it was said to be enormously significant at the time: 'the most radical analysis of Britain's plight offered by any Labour leader since 1945,' according to the post-match punditry of Patrick Wintour in the Guardian. It was the speech that was going to reframe the public debate of capitalism, with its distinction between predators and producers.

But perhaps the most striking section of that speech was when Miliband dwelt on the past. There had been speculation that he was going to apologise for the mistakes made by the last Labour government. But he had much older fish to fry. 'Some of what happened in the 1980s was right,' he told conference. 'It was right to let people buy their council houses. It was right to cut taxes of 60, 70, 80 per cent. And it was right to change the rules on the closed shop, on strikes before ballots.'

Thirty years on, and Labour was still trying to get over its failed strategy in the 1980s. Before straightening its tie and going out to make the same mistakes all over again.

Thursday, 16 July 2015

Leader of the gang

There's been a lot of very excited comment in the last day or so about how Jeremy Corbyn is on course to win in the Labour Party's leadership election. Round these parts, however, we try not to get over-excited. As The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy used to advise: Don't panic. Corbyn will not be the next leader. So who will?

Back in early April, I predicted that - following its inevitable defeat in the coming election - the party would opt for a female leader and choose either Yvette Cooper or Rachel Reeves. Since Reeves isn't standing, I'm going to have to stick with my other suggestion and predict a Cooper victory in September. She won't lead on first-preference votes, but I expect her to come through the middle and win in the third round.

She is not, in my opinion, the best choice that the Labour Party could make. But none of the three outsiders I nominated - Gloria de Piero, John Mann, Ben Bradshaw - took up the challenge, and we have instead the current dull slate of candidates. Of whom Cooper is probably the least poor.

Andy Burnham is the boring and unexceptional option, Jeremy Corbyn is the fascinating and catastrophic choice, and Liz Kendall - well, I don't know. I just don't get Kendall. In print, her arguments have some validity, but her delivery is as about as convincing as a student teacher. I simply can't picture her as a party leader, let alone prime minister. And I can at least see Cooper as a leader.

But Labour should have learnt at least one lesson from the last five miserable years. When the electorate tell you that your leader has a problem with credibility and image, then you should listen to them. Every single poll showed that Ed Miliband's popularity trailed that of his party. And Labour's response was to give us more Miliband, as though it were our fault: we simply hadn't understood how wonderful he was.

He wasn't. He was dreadful. And since his colleagues couldn't summon up the courage to remove him, they should have insisted on the next best strategy: don't focus exclusively on the leader.

The party would be wise to do so this time. Cooper is not a great candidate, by any means (though she's a huge improvement on Miliband), and she's not surrounded by the best generation of politicians in Labour's history. But then, the government - with a couple of exceptions - ain't much cop either. Collectively, Labour don't look any more incompetent than the Tories.

Here's a potential shadow cabinet line-up, with their counterparts in the real cabinet shown in brackets:

A couple of other things left over from Ed Miliband's doomed leadership.

The change in the rules for the election of the leader was a mistake. The idea of one-member one-vote was fine, but there should be some way of whittling down the cast-list before it goes to the vote. Much the same as the Tories do, where the MPs choose two candidates who are then put to the party membership. The point is that a leader spends most of their time working with parliamentary colleagues; if they can't command support there, then they stand no chance, regardless of what the party in the country thinks.

I know this doesn't always work smoothly in the Conservative Party. There have been two leadership elections since William Hague introduced the system, and one of them resulted in the absurd elevation of Iain Duncan Smith. I also know that Labour has a rule that a candidate needs the nominations of 20 per cent of MPs - but in the cases of Diane Abbott and Jeremy Corbyn, we have seen how flawed this would-be filtering mechanism is.

And finally, the one thing that Miliband did get right was his promotion of new talent. In 2011 I noted the appearance on consecutive days on Question Time and Any Questions of Gloria de Piero and Rachel Reeves, both of whom had only been elected the previous year and both of whom were already in the shadow cabinet.

'These are the potential stars of the next parliament being given a chance to get a bit of exposure and experience,' I wrote. I added: 'The unmistakable impression, however, is that Labour's given up on the idea of opposition for the immediate future and is building for the world after the next election.'

That world's now arrived, and Miliband's investment in apprentice politicians may now pay off.

Back in early April, I predicted that - following its inevitable defeat in the coming election - the party would opt for a female leader and choose either Yvette Cooper or Rachel Reeves. Since Reeves isn't standing, I'm going to have to stick with my other suggestion and predict a Cooper victory in September. She won't lead on first-preference votes, but I expect her to come through the middle and win in the third round.

She is not, in my opinion, the best choice that the Labour Party could make. But none of the three outsiders I nominated - Gloria de Piero, John Mann, Ben Bradshaw - took up the challenge, and we have instead the current dull slate of candidates. Of whom Cooper is probably the least poor.

Andy Burnham is the boring and unexceptional option, Jeremy Corbyn is the fascinating and catastrophic choice, and Liz Kendall - well, I don't know. I just don't get Kendall. In print, her arguments have some validity, but her delivery is as about as convincing as a student teacher. I simply can't picture her as a party leader, let alone prime minister. And I can at least see Cooper as a leader.

But Labour should have learnt at least one lesson from the last five miserable years. When the electorate tell you that your leader has a problem with credibility and image, then you should listen to them. Every single poll showed that Ed Miliband's popularity trailed that of his party. And Labour's response was to give us more Miliband, as though it were our fault: we simply hadn't understood how wonderful he was.

He wasn't. He was dreadful. And since his colleagues couldn't summon up the courage to remove him, they should have insisted on the next best strategy: don't focus exclusively on the leader.

The party would be wise to do so this time. Cooper is not a great candidate, by any means (though she's a huge improvement on Miliband), and she's not surrounded by the best generation of politicians in Labour's history. But then, the government - with a couple of exceptions - ain't much cop either. Collectively, Labour don't look any more incompetent than the Tories.

Here's a potential shadow cabinet line-up, with their counterparts in the real cabinet shown in brackets:

- Yvette Cooper - leader (David Cameron)

- Chuka Umunna - shadow chancellor (George Osborne)

- Alan Johnson - foreign affairs (Philip Hammond)

- Rachel Reeves - business (Sajid Javid)

- John Mann - home affairs (Theresa May)

- Keir Starmer - justice (Michael Gove)

- Hilary Benn - health (Jeremy Hunt)

- Caroline Flint - education (Nicky Morgan)

- Andy Burnham - work and pensions (Iain Duncan Smith)

- Gloria de Piero - energy and climate change (Amber Rudd)

- Liz Kendall - transport (Patrick McLoughlin)

- Dan Jarvis - defence (Michael Fallon)

- Michael Meacher - environment and food (Liz Truss)

- Stella Creasey - communities and local government (Greg Clark)

- Chris Bryant - culture, media and sport (John Whittingdale)

- Emma Reynolds - women and equalities (Nicky Morgan, again)

- Chris Leslie - shadow first secretary (Greg Hands)

- Jeremy Corbyn - international development (Justine Greening)

- Rosie Winterton - chief whip (Mark Harper)

- Ben Bradshaw - leader of the house (Chris Grayling)

A couple of other things left over from Ed Miliband's doomed leadership.

The change in the rules for the election of the leader was a mistake. The idea of one-member one-vote was fine, but there should be some way of whittling down the cast-list before it goes to the vote. Much the same as the Tories do, where the MPs choose two candidates who are then put to the party membership. The point is that a leader spends most of their time working with parliamentary colleagues; if they can't command support there, then they stand no chance, regardless of what the party in the country thinks.

I know this doesn't always work smoothly in the Conservative Party. There have been two leadership elections since William Hague introduced the system, and one of them resulted in the absurd elevation of Iain Duncan Smith. I also know that Labour has a rule that a candidate needs the nominations of 20 per cent of MPs - but in the cases of Diane Abbott and Jeremy Corbyn, we have seen how flawed this would-be filtering mechanism is.

And finally, the one thing that Miliband did get right was his promotion of new talent. In 2011 I noted the appearance on consecutive days on Question Time and Any Questions of Gloria de Piero and Rachel Reeves, both of whom had only been elected the previous year and both of whom were already in the shadow cabinet.

'These are the potential stars of the next parliament being given a chance to get a bit of exposure and experience,' I wrote. I added: 'The unmistakable impression, however, is that Labour's given up on the idea of opposition for the immediate future and is building for the world after the next election.'

That world's now arrived, and Miliband's investment in apprentice politicians may now pay off.

Monday, 22 June 2015

'Satan's bearded folk singer' *

In the article published in the Sunday Times yesterday and signed by both George Osborne and Iain Duncan Smith, they begin by quoting David Blunkett's views on the benefits system: 'bonkers'.

I've always had a lot of time for Blunkett. I seldom agree with him, but he's generally worth listening to (except when he's claiming that Ed Miliband was the new Clement Attlee). His instincts are those of the old working class, which made him an unusual figure in the New Labour Party. He was clearly aware of that position, that he was out of step with the modern leadership, which is why - for all his reputation as a plain-speaker - he buttoned his lip on some subjects altogether: when, for example, was the last time you heard him mention homosexuality?

More broadly, however, he has consistently voiced perceptions that challenge any sense of left-wing complacency. And, as the excitement over the Labour leadership election mounts, I'm reminded of a line from 2000, published in his book The Blunkett Tapes:

I've always had a lot of time for Blunkett. I seldom agree with him, but he's generally worth listening to (except when he's claiming that Ed Miliband was the new Clement Attlee). His instincts are those of the old working class, which made him an unusual figure in the New Labour Party. He was clearly aware of that position, that he was out of step with the modern leadership, which is why - for all his reputation as a plain-speaker - he buttoned his lip on some subjects altogether: when, for example, was the last time you heard him mention homosexuality?

More broadly, however, he has consistently voiced perceptions that challenge any sense of left-wing complacency. And, as the excitement over the Labour leadership election mounts, I'm reminded of a line from 2000, published in his book The Blunkett Tapes:

'The liberal left believe that if they think hard enough that the world is with them, then somehow it is, whereas the very opposite is true. Britain is an innately conservative country and we need to win people over to progressive politics.'* The 'Satan's bearded folk singer' quote comes, of course, from the late Linda Smith.

Friday, 5 June 2015

Yesterday Once More: Tougher sanctions are needed

This just in...

'Welfare reforms which will compel lone parents and the disabled to attend repeated job advice interviews or forfeit benefit will confront head-on the "poverty of expectation" sidelining thousands of Britain's poorest people, the government insisted yesterday...

'Ministers argue that it is reasonable to make a job advice interview a condition of claiming benefits, since many claimants are unaware of support the state can provide to help them avoid the poverty trap. Tougher sanctions are needed, they believe, to encourage the one million lone parents on income support and 2.8 million people on disability benefits back into work...

'He added: "It is the poverty of ambition and poverty of expectation that is debilitating. If you are going to crack that, you have got to confront it and do some things which people think are tough..."

'Mencap and the mental health charity Mind yesterday claimed compulsory interviews would leave millions of vulnerable disabled people in fear of losing benefits.

'There was anger from disability campaigners over plans to tighten the criteria for incapacity benefit, which ministers suspect is abused as an early retirement subsidy. Campaigners fear many genuinely disabled people will no longer qualify...

'The Tories accused the government of "talking tough" but not "acting tough". Shadow social security secretary Iain Duncan Smith said the whole success of the welfare-to-work programme depended on new jobs being created. But new employment legislation was boosting the burden on business.'

'Welfare reforms which will compel lone parents and the disabled to attend repeated job advice interviews or forfeit benefit will confront head-on the "poverty of expectation" sidelining thousands of Britain's poorest people, the government insisted yesterday...

'Ministers argue that it is reasonable to make a job advice interview a condition of claiming benefits, since many claimants are unaware of support the state can provide to help them avoid the poverty trap. Tougher sanctions are needed, they believe, to encourage the one million lone parents on income support and 2.8 million people on disability benefits back into work...

'He added: "It is the poverty of ambition and poverty of expectation that is debilitating. If you are going to crack that, you have got to confront it and do some things which people think are tough..."

'Mencap and the mental health charity Mind yesterday claimed compulsory interviews would leave millions of vulnerable disabled people in fear of losing benefits.

'There was anger from disability campaigners over plans to tighten the criteria for incapacity benefit, which ministers suspect is abused as an early retirement subsidy. Campaigners fear many genuinely disabled people will no longer qualify...

'The Tories accused the government of "talking tough" but not "acting tough". Shadow social security secretary Iain Duncan Smith said the whole success of the welfare-to-work programme depended on new jobs being created. But new employment legislation was boosting the burden on business.'

- extracted from Lucy Ward, '"Harsh" rules to benefit poor',

Guardian 11 February 1999

Note: The 'He' who is quoted in the third paragraph is Alistair Darling, then social security secretary in Tony Blair's Labour government.

Tuesday, 28 April 2015

We're not all Rob Roys

Since the only story in the general election is the performance of the Scottish National Party, I thought I'd have a look through my archive of political quotes to see what's been said on the subject of Scotland from outside:

'One only has to go to Scotland for a moment to understand the Scottishness of Scotland.' - John Major (1992)

'Scotland needs the Labour Party as much as Sicily needs the mafia.' - Malcolm Rifkind (1992)

'I love Scotland. It's a loony sort of place.' - Screaming Lord Sutch (1998)

'A wee, pretendy parliament.' - Billy Connolly (2000)

'I would rather have played rugby for Scotland than be prime minister.' - Iain Duncan Smith (2002)

'Ghastly.' - Camilla Parker-Bowles on the Scottish Parliament building (2004)

'We need Crossrail to keep London's economy ticking over, so that we can continue to pay for the Scottish to live the lifestyle to which they are accustomed.' - Ken Livingstone (2006)

And here's a pot speaking about the kettle that is Alex Salmond:

'A man who fell in love with himself at an early age and has been faithful ever since.' - Alastair Campbell (2008)

'One only has to go to Scotland for a moment to understand the Scottishness of Scotland.' - John Major (1992)

'Scotland needs the Labour Party as much as Sicily needs the mafia.' - Malcolm Rifkind (1992)

'I love Scotland. It's a loony sort of place.' - Screaming Lord Sutch (1998)

'A wee, pretendy parliament.' - Billy Connolly (2000)

'I would rather have played rugby for Scotland than be prime minister.' - Iain Duncan Smith (2002)

'Ghastly.' - Camilla Parker-Bowles on the Scottish Parliament building (2004)

'We need Crossrail to keep London's economy ticking over, so that we can continue to pay for the Scottish to live the lifestyle to which they are accustomed.' - Ken Livingstone (2006)

And here's a pot speaking about the kettle that is Alex Salmond:

'A man who fell in love with himself at an early age and has been faithful ever since.' - Alastair Campbell (2008)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)