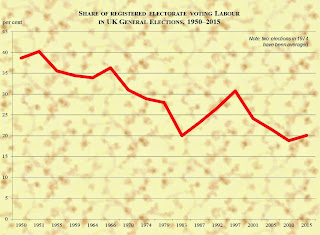

It's been a couple of weeks since I put a graph on this blog. So here's one showing the proportion of the electorate who voted for the Labour Party in general elections between 1950 and 2015:

There are a couple of blips in there - down with Michael Foot in 1983, up with Tony Blair in 1997 - but the underlying, downward trend is unmistakeable. And that seems to me pretty much the key issue that Labour ought to be considering.

Obviously this decline in interest is not confined to Labour. The share achieved by both major parties has been falling fairly steadily, eroded by the growth of minor parties (Liberal and nationalist) from the 1960s onwards, and by low turnout more recently.

Here's another chart, showing the performance of both Labour and Conservative Parties.

Like high-street shopping, politics isn't what it used to be. There's still room for a specialist, niche supplier such as the SNP, and for the purely functional Tesco Metro or Sainsbury Local represented by the Conservatives. But Labour is in danger of looking like Woolworth's - trying to do so many things, all of them adequately at best, that no one can remember why it's there.

Because the decline is, I believe, a bigger problem for Labour than it is for the Tories. Generally speaking, the Conservatives don't need to inspire their supporters in the same way; normally they can fall back on their reputation for economic competence. Despite Harold Wilson's boast that Labour had become 'the natural party of government', the default setting in British politics is Tory.

To illustrate the point: this election was not the first since 1950 in which the result was unexpected. The same was true in 1970 and again in 1992. And in all of these, the surprise was that the Conservative Party won. (Or, possibly, the Labour Party lost.)

The Labour equivalent of these surprise victories is negative: an unexpectedly unconvincing win, as in 1964 and 1974.

To find an exception, you have to go back to the Labour victory in 1945, before opinion polls were properly established. And that election was held in quite extraordinary circumstances - to start with, it was the first for a decade. It did, though, illustrate Labour's great challenge: unlike the Tories, in order to win power, it really needs to articulate a vision of a better future.

As Wilson also pointed out: 'The Labour Party is a moral crusade or it is nothing.'

The task in choosing a new leader is to find someone who can articulate a sense of hope for the future, to persuade somewhere around a quarter of the electorate that he or she can help us build a better society.

It doesn't sound too difficult, put like that. But clearly it is. And of those who have so far declared that they would like to be candidates, I can't say that any have so far inspired me.

No comments:

Post a Comment