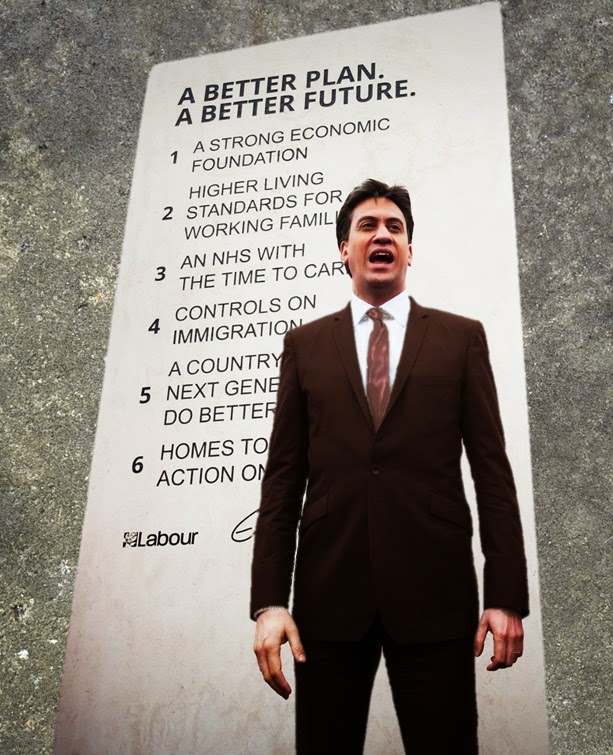

'On immigration and Labour's trade union link, Ed Miliband's leadership actually represented a shift to the right from the Blair years,' wrote Owen Jones in the Guardian last week.

Certainly as far as immigration goes, he's perfectly correct. But then, in purely political terms, perhaps Miliband was right to move the party's position.

In 2004 eight East European countries (plus Malta and Cyprus) joined the European Union, the largest enlargement the organisation has ever experienced. This was the occasion when the likes of Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic joined, and the occasion that sparked a steep rise in immigration into the UK from European countries.

The then prime minister, Tony Blair, was enthusiastic about the arrival of the new member states. This was, he declared: 'A good day not just for Poland, Latvia and Cyprus, but also for Peterborough, Leeds and Carlisle.'

So how did that work out politically? Well, the good news is that Labour still holds four of the five parliamentary constituencies in Leeds. But the fifth - Leeds North West - fell to the Liberal Democrats in 2005, and has been retained by them ever since.

Meanwhile both Peterborough and Carlisle, which were held by Labour at the time of Blair's comments, have fallen to the Conservative Party, in 2005 and 2010 respectively.

From a Labour Party perspective, that seems to be the problem with the public - they don't appreciate what's good for them.

Saturday, 30 May 2015

Thursday, 28 May 2015

Millionaires - an endangered species

A report from the Daily Express in 1954:

'There are now only 36 people left in the millionaire class of taxpayers in Britain. A year ago there were 60. And in 1939 the number was 1,024.

'Yesterday Inland Revenue figures for the year ended March 31 1953 showed that only 36 people had incomes of more than £6,000 a year after tax. A tax official said: "To be left with £6,000 means you must earn at least £56,000 or have a million pounds invested at about five per cent."

'The report covers the first full year's drive against savers who had escaped tax on interest on savings in Post Office and other banks - and showed that more than £16,000,000 had been raked in.'

'There are now only 36 people left in the millionaire class of taxpayers in Britain. A year ago there were 60. And in 1939 the number was 1,024.

'Yesterday Inland Revenue figures for the year ended March 31 1953 showed that only 36 people had incomes of more than £6,000 a year after tax. A tax official said: "To be left with £6,000 means you must earn at least £56,000 or have a million pounds invested at about five per cent."

'The report covers the first full year's drive against savers who had escaped tax on interest on savings in Post Office and other banks - and showed that more than £16,000,000 had been raked in.'

Wednesday, 27 May 2015

Will no one rid us of this tedious pundit?

'The Tories who witnessed the Major years still bear some scar tissue,' writes Simon Heffer in the New Statesman, as he commences his analysis of the new government's position.

Well, yes, and much of it was inflicted by him and others in the supposedly loyal Tory press, still worshipping at the shrine of the fallen idol, having never got over the emotional shock of witnessing her departure from Downing Street. When John Major was told during the 1992 election campaign that the Conservative Party was six points behind Labour in the opinion polls, he replied: 'Of those six points, three are the fault of Simon Heffer and the other three are Frank Johnson's fault.'

Heffer was then the deputy editor of the Daily Telegraph and the relentless sniping from that newspaper and from the Daily Mail did a huge amount of damage to Major's government. It'll be interesting to see how much they've learned from the experience.

Meanwhile, though, I do wonder why any publication continues to pay Heffer money for his views, given how ludicrously inept his assessments are. I know most commentators, having spent far too long reading opinion polls, called the recent election wrong, but Heffer is way beyond that. He is willfully blind to reality, his perception distorted by dogma in a way that would have caused embarrassment to a member of the Workers' Revolutionary Party in the days of Gerry Healy.

In May last year, following the European elections, Heffer wrote about the urgent need for the Tories to form an electoral pact with Ukip. In constituencies such as Nigel Farage's promised land of Thanet South, he said, 'there is nothing to be gained by putting up a novice candidate against him'. Foolishly, the Conservative party ignored his wise advice, fielded their own candidate and, er, won the seat.

Heffer's article concluded: 'If the Tories have any sense, they will start talking about such an arrangement now. For if, next week, Ukip wins the Newark by-election and the Tories descend into panic, David Cameron might find himself with no other option.' Needless to say, the Conservative Party won the Newark by-election, with a handsome 7,400 majority. In the general election, they increased that to 18,500, with Ukip beaten into third place by Labour.

But the great sage was undeterred. He still knew better, and mere facts weren't going to get in his way. This is him in August last year. 'Although they [the Tories] have doggedly refused to entertain the idea, they will have to consider an electoral pact with Ukip, or face at least five years out of government.' Consequently, 'the party's grandees will, I am convinced, make a humiliating U-turn.'

If David Cameron would only reach out to Ukip, 'he wouldn't just keep himself in Downing Street, but would reunite a conservative coalition - which, I am sure, is really what the country wants.'

All that certainty, all that absolute self-confidence, all that nonsense.

But then this is the man who backed John Redwood's bid for the Conservative leadership in 1995. He has been consistently wrong for over twenty years now. Why is he still considered employable?

Well, yes, and much of it was inflicted by him and others in the supposedly loyal Tory press, still worshipping at the shrine of the fallen idol, having never got over the emotional shock of witnessing her departure from Downing Street. When John Major was told during the 1992 election campaign that the Conservative Party was six points behind Labour in the opinion polls, he replied: 'Of those six points, three are the fault of Simon Heffer and the other three are Frank Johnson's fault.'

Heffer was then the deputy editor of the Daily Telegraph and the relentless sniping from that newspaper and from the Daily Mail did a huge amount of damage to Major's government. It'll be interesting to see how much they've learned from the experience.

Meanwhile, though, I do wonder why any publication continues to pay Heffer money for his views, given how ludicrously inept his assessments are. I know most commentators, having spent far too long reading opinion polls, called the recent election wrong, but Heffer is way beyond that. He is willfully blind to reality, his perception distorted by dogma in a way that would have caused embarrassment to a member of the Workers' Revolutionary Party in the days of Gerry Healy.

In May last year, following the European elections, Heffer wrote about the urgent need for the Tories to form an electoral pact with Ukip. In constituencies such as Nigel Farage's promised land of Thanet South, he said, 'there is nothing to be gained by putting up a novice candidate against him'. Foolishly, the Conservative party ignored his wise advice, fielded their own candidate and, er, won the seat.

Heffer's article concluded: 'If the Tories have any sense, they will start talking about such an arrangement now. For if, next week, Ukip wins the Newark by-election and the Tories descend into panic, David Cameron might find himself with no other option.' Needless to say, the Conservative Party won the Newark by-election, with a handsome 7,400 majority. In the general election, they increased that to 18,500, with Ukip beaten into third place by Labour.

But the great sage was undeterred. He still knew better, and mere facts weren't going to get in his way. This is him in August last year. 'Although they [the Tories] have doggedly refused to entertain the idea, they will have to consider an electoral pact with Ukip, or face at least five years out of government.' Consequently, 'the party's grandees will, I am convinced, make a humiliating U-turn.'

If David Cameron would only reach out to Ukip, 'he wouldn't just keep himself in Downing Street, but would reunite a conservative coalition - which, I am sure, is really what the country wants.'

All that certainty, all that absolute self-confidence, all that nonsense.

But then this is the man who backed John Redwood's bid for the Conservative leadership in 1995. He has been consistently wrong for over twenty years now. Why is he still considered employable?

Sunday, 24 May 2015

Yesterday's News Today: Fascist leader arrested

This is the front page of the Daily Sketch from 24 May 1940, seventy-five years ago today:

There is something rather impressive about the fact that it took the authorities quite so long to arrest Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists. This was, after all, nearly nine months after the declaration of war, which says something for the much vaunted British sense of tolerance.

Friday, 22 May 2015

The mystery of the three million

One of the central concerns about Britain leaving the European Union is that it will put British jobs at risk. How many jobs, precisely? Or, if not precisely, then at least roughly?

For clarification on this burning issue of our time, naturally I turned to the acknowledged expert on economics in modern politics, the man who spent ten years as chancellor of the exchequer before becoming prime minister.

During the 1997 election campaign, Gordon Brown warned that divisions and uncertainty in the Conservative Party threatened 'the three-and-a-half million jobs that relied on Europe'. But that seems to have been an over-estimate, because four years later he was arguing that 'over three quarters of a million UK companies trade with the rest of the European Union - half our total trade - with three million jobs affected'.

So it's three million? Yes, that must be right. Because that was the figure Brown was still citing in 2005, and then again in the 2010 election campaign: 'Three million jobs depend on our membership of the European Union.'

And in March this year, Brown made the same point: 'We must tell the truth about the three million jobs, 25,000 companies, £200 billion of annual exports and the £450 billion of inward investment linked to Europe.'

(Incidentally, that '25,000 companies' is a bit worrying, don't you think? In 2001 it was 'over three quarters of a million companies'. What on earth has happened to our economy?)

Coming back to those three million jobs, though. It's not just Gordon Brown who quotes this figure. It's bandied around all the time by those who support British membership of the EU. It was quoted, for example, by Tim Farron on Question Time last night.

But I'm no economist, and there's something I don't fully understand. We had, we were told, the longest period of uninterrupted growth in our history, followed by the worst recession in living memory, and then a recovery that's either the envy of the developed world or a fragile property-fuelled bubble (depending on taste).

Things have changed so much. Back in 1997 we had around 26 million people employed in Britain. Now it's over 30 million.

And yet somehow, inexplicably, the number of jobs dependent on the EU doesn't seem to have moved an inch in all that time. It didn't go up in the good times; it hasn't come down with all the problems in the Euro-zone.

It just sits there, unchanging and - perhaps more to the point - unchallenged. Puzzling, isn't it?

For clarification on this burning issue of our time, naturally I turned to the acknowledged expert on economics in modern politics, the man who spent ten years as chancellor of the exchequer before becoming prime minister.

During the 1997 election campaign, Gordon Brown warned that divisions and uncertainty in the Conservative Party threatened 'the three-and-a-half million jobs that relied on Europe'. But that seems to have been an over-estimate, because four years later he was arguing that 'over three quarters of a million UK companies trade with the rest of the European Union - half our total trade - with three million jobs affected'.

So it's three million? Yes, that must be right. Because that was the figure Brown was still citing in 2005, and then again in the 2010 election campaign: 'Three million jobs depend on our membership of the European Union.'

And in March this year, Brown made the same point: 'We must tell the truth about the three million jobs, 25,000 companies, £200 billion of annual exports and the £450 billion of inward investment linked to Europe.'

(Incidentally, that '25,000 companies' is a bit worrying, don't you think? In 2001 it was 'over three quarters of a million companies'. What on earth has happened to our economy?)

Coming back to those three million jobs, though. It's not just Gordon Brown who quotes this figure. It's bandied around all the time by those who support British membership of the EU. It was quoted, for example, by Tim Farron on Question Time last night.

But I'm no economist, and there's something I don't fully understand. We had, we were told, the longest period of uninterrupted growth in our history, followed by the worst recession in living memory, and then a recovery that's either the envy of the developed world or a fragile property-fuelled bubble (depending on taste).

Things have changed so much. Back in 1997 we had around 26 million people employed in Britain. Now it's over 30 million.

And yet somehow, inexplicably, the number of jobs dependent on the EU doesn't seem to have moved an inch in all that time. It didn't go up in the good times; it hasn't come down with all the problems in the Euro-zone.

It just sits there, unchanging and - perhaps more to the point - unchallenged. Puzzling, isn't it?

Wednesday, 20 May 2015

Careful with that axe, Kenneth

I think I may have found the first public appearance of a British politician bearing a guitar. This is a notice from the Manchester Guardian in May 1956:

A new era in British politics has arrived. The Labour Party, reading the portents of thin election meetings and fat queues at the music hall, has taken to the guitar. Last night Mr Kenneth Younger, a former minister of state, sweetened his party's political broadcast on the eve of the municipal elections with a parody of 'Oh dear, what can the matter be?' sung in a pleasant tenor voice and accompanied by himself on a guitar.

It is apparent that Labour, whose broadcasts in previous elections were accused of having lost the Battle of Slickness to the Conservatives, has decided to temper the earnestness of politics with the juke box.Although I've never seen this broadcast, it all sounds quite harmless, even endearing. Until you realise that venturing onto this slippery slope would one day plunge us into the world of the (self-proclaimed) first rock 'n' roll prime minister...

Tuesday, 19 May 2015

Black Sash: heroines of the anti-apartheid struggle

Today is the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of Black Sash, one of the most inspiring campaign groups in modern history.

Back in 1955, the National Party government of South Africa was extending the implementation of apartheid, and Black Sash was formed to resist constitutional changes that were intended to entrench white rule; hence its original name of the Women's Defence of the Constitution League.The women who became involved over the ensuing decades were predominantly white, middle-class and English-speaking. Therein lies part of the reason why they're so inspiring. From a position of privilege, they had everything to lose. There was personal risk for them in attracting the attentions of the police and the authorities, and no material benefit in the change for which they campaigned.

But mostly Black Sash are so impressive because of the tactics they adopted. Initially their impact came in the silent witness they bore, as seen in the photograph above, haunting the public appearances of politicians, their black sashes a symbol of dissent, their silence the sound of defiance.

Their campaign attracted international attention almost from the outset. Here's an early account from the Manchester Guardian sixty years ago:

Their technique is to stand solemnly and silently at any gateway through which a minister has to pass. They bow their heads. They wear a black sash across their body. Everything about them is sombre and cheerless. Then when the minister arrives they still do nothing. But they do it more emphatically. Consequently their dour appearance tends to introduce a mournful gloom into whatever is going on.Later, placards were carried, still in silence, as the women drew attention to specific cases of abuse and protested against the evils of apartheid more generally. Most powerfully these demonstrations were staged outside courtrooms, insisting that justice be seen to be done.

Meanwhile a network of offices was being built across the country, providing support and advice for those suffering under apartheid, as the government's attempts to suppress freedom grew ever more violent. Political witness was augmented by practical assistance.

Black Sash was also, for many both inside and outside South Africa, one of the few sources of reliable information about the realities of what was happening in the country. Its testimony was sufficiently powerful and authoritative that eventually the government banned newspapers like the Sowetan and the Weekly Mail from even quoting the organisation.

As the struggle intensified in the last desperate years of National Party rule, so the group's work became ever more vital. In the words of one activist: 'It's inspiring and it's heartbreaking. We're living history every day.'

In the post-apartheid era, Black Sash continues to campaign for human rights and for progress. Because the struggle is not yet over. As their website explains: 'South Africa cannot be free as long as the majority of its people continue to live under conditions of deprivation and injustice.'

Nelson Mandela called them 'the conscience of white South Africa', which is a pretty fine compliment. Even so, I hesitated before quoting it, because - in Britain at least - the fight against apartheid has been so personalised that it sometimes feels as though Mandela were solely responsible for the overthrow of the system.

In the process, the contributions made by others - and by organisations other than the ANC - are all too often overlooked. To help rectify that, might I suggest a visit to the Black Sash website?

Monday, 18 May 2015

Decline of a moral crusade

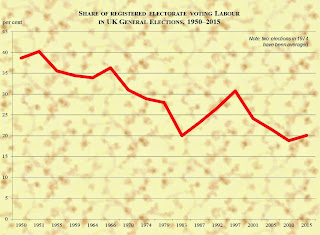

It's been a couple of weeks since I put a graph on this blog. So here's one showing the proportion of the electorate who voted for the Labour Party in general elections between 1950 and 2015:

There are a couple of blips in there - down with Michael Foot in 1983, up with Tony Blair in 1997 - but the underlying, downward trend is unmistakeable. And that seems to me pretty much the key issue that Labour ought to be considering.

Obviously this decline in interest is not confined to Labour. The share achieved by both major parties has been falling fairly steadily, eroded by the growth of minor parties (Liberal and nationalist) from the 1960s onwards, and by low turnout more recently.

Here's another chart, showing the performance of both Labour and Conservative Parties.

Like high-street shopping, politics isn't what it used to be. There's still room for a specialist, niche supplier such as the SNP, and for the purely functional Tesco Metro or Sainsbury Local represented by the Conservatives. But Labour is in danger of looking like Woolworth's - trying to do so many things, all of them adequately at best, that no one can remember why it's there.

Because the decline is, I believe, a bigger problem for Labour than it is for the Tories. Generally speaking, the Conservatives don't need to inspire their supporters in the same way; normally they can fall back on their reputation for economic competence. Despite Harold Wilson's boast that Labour had become 'the natural party of government', the default setting in British politics is Tory.

To illustrate the point: this election was not the first since 1950 in which the result was unexpected. The same was true in 1970 and again in 1992. And in all of these, the surprise was that the Conservative Party won. (Or, possibly, the Labour Party lost.)

The Labour equivalent of these surprise victories is negative: an unexpectedly unconvincing win, as in 1964 and 1974.

To find an exception, you have to go back to the Labour victory in 1945, before opinion polls were properly established. And that election was held in quite extraordinary circumstances - to start with, it was the first for a decade. It did, though, illustrate Labour's great challenge: unlike the Tories, in order to win power, it really needs to articulate a vision of a better future.

As Wilson also pointed out: 'The Labour Party is a moral crusade or it is nothing.'

The task in choosing a new leader is to find someone who can articulate a sense of hope for the future, to persuade somewhere around a quarter of the electorate that he or she can help us build a better society.

It doesn't sound too difficult, put like that. But clearly it is. And of those who have so far declared that they would like to be candidates, I can't say that any have so far inspired me.

There are a couple of blips in there - down with Michael Foot in 1983, up with Tony Blair in 1997 - but the underlying, downward trend is unmistakeable. And that seems to me pretty much the key issue that Labour ought to be considering.

Obviously this decline in interest is not confined to Labour. The share achieved by both major parties has been falling fairly steadily, eroded by the growth of minor parties (Liberal and nationalist) from the 1960s onwards, and by low turnout more recently.

Here's another chart, showing the performance of both Labour and Conservative Parties.

Like high-street shopping, politics isn't what it used to be. There's still room for a specialist, niche supplier such as the SNP, and for the purely functional Tesco Metro or Sainsbury Local represented by the Conservatives. But Labour is in danger of looking like Woolworth's - trying to do so many things, all of them adequately at best, that no one can remember why it's there.

Because the decline is, I believe, a bigger problem for Labour than it is for the Tories. Generally speaking, the Conservatives don't need to inspire their supporters in the same way; normally they can fall back on their reputation for economic competence. Despite Harold Wilson's boast that Labour had become 'the natural party of government', the default setting in British politics is Tory.

To illustrate the point: this election was not the first since 1950 in which the result was unexpected. The same was true in 1970 and again in 1992. And in all of these, the surprise was that the Conservative Party won. (Or, possibly, the Labour Party lost.)

The Labour equivalent of these surprise victories is negative: an unexpectedly unconvincing win, as in 1964 and 1974.

To find an exception, you have to go back to the Labour victory in 1945, before opinion polls were properly established. And that election was held in quite extraordinary circumstances - to start with, it was the first for a decade. It did, though, illustrate Labour's great challenge: unlike the Tories, in order to win power, it really needs to articulate a vision of a better future.

As Wilson also pointed out: 'The Labour Party is a moral crusade or it is nothing.'

The task in choosing a new leader is to find someone who can articulate a sense of hope for the future, to persuade somewhere around a quarter of the electorate that he or she can help us build a better society.

It doesn't sound too difficult, put like that. But clearly it is. And of those who have so far declared that they would like to be candidates, I can't say that any have so far inspired me.

Sunday, 17 May 2015

Thought for the day

As newly elected MPs gathered this week at Westminster, I was reminded of Shona McIsaac, who served as the Labour member for Cleethorpes between 1997 and 2010. This is her in 1998, offering an honest recognition of her place in the bigger picture:

I was voted in because I was a Labour candidate. Few people, if any, voted for me as a person. I have a sneaking suspicion that my husband voted for me because I was me, and I voted for me because I was me. But if I had not been the Labour Party candidate, I would not have voted for me either.Humility is a much underrated political virtue.

Saturday, 16 May 2015

And the nominees are...

I'm not overwhelmed by the list of MPs who have thus far declared they wish to be candidates for the leadership election. So here's a trio of others who might wish to buy a hat and then find a ring to throw it into:

John Mann - age 55, MP since 2001, born in Leeds, economics degree from Manchester University. Spent several years on the Treasury Select Committee. Would have fitted into a pre-Tony Blair version of the Labour Party in a solid, moral sort of way. Mann is awkward: in 2005 he denounced Lakshmi Mittal, the billionaire Labour donor, for pay and conditions in his Kazakhstan mines. Also very active in criticising the abuse of parliamentary expenses.

Ben Bradshaw - age 54, MP since 1997, born in London, German degree from Sussex University. Had a (not very distinguished) government career, including health minster and a short stint as culture secretary. Too Blairite to stand a chance in winning the leadership and too London to win over the electorate. But he's included here because he's by far the best-dressed MP of any party, and that really should count for something in an age of appearances. He's also good-looking enough to play a doctor in a daytime soap opera.

Gloria de Piero - age 42, MP since 2010, born in Bradford, social science degree from University of Westminster. Former presenter on GMTV, having previously worked on big, serious political programmes. The attempt to find someone who 'connects' with voters and understands the concept of 'aspirations' surely takes us to a 'working-class, free-school-meal girl from Bradford' who's done well for herself. Particularly with all that media experience.

John Mann - age 55, MP since 2001, born in Leeds, economics degree from Manchester University. Spent several years on the Treasury Select Committee. Would have fitted into a pre-Tony Blair version of the Labour Party in a solid, moral sort of way. Mann is awkward: in 2005 he denounced Lakshmi Mittal, the billionaire Labour donor, for pay and conditions in his Kazakhstan mines. Also very active in criticising the abuse of parliamentary expenses.

Ben Bradshaw - age 54, MP since 1997, born in London, German degree from Sussex University. Had a (not very distinguished) government career, including health minster and a short stint as culture secretary. Too Blairite to stand a chance in winning the leadership and too London to win over the electorate. But he's included here because he's by far the best-dressed MP of any party, and that really should count for something in an age of appearances. He's also good-looking enough to play a doctor in a daytime soap opera.

Friday, 15 May 2015

The pressure of being a candidate

The abrupt withdrawal of Chuka Umunna from the Labour leadership race, 'citing the impact the increased level of attention would have on himself and those close to him', brings to mind an earlier case.

Four decades back, the defeat of Edward Heath's Conservative Party in two elections in 1974 prompted talk of a change in leadership. There was an obvious candidate, but it turned out he couldn't take the heat. The following account is extracted from my book Crisis? What Crisis?:

‘He will have to go’ was the Daily

Mail’s verdict on Edward Heath after he lost his second general election in a row,

and his third in total, and Keith Joseph was the right’s front-runner in the

succession stakes, an intelligent, if awkward, man who had already distanced

himself from the failures of the past and who offered a clear, determined

direction forward.

And then he threw it away. His first post-election speech was in Edgbaston, not far from the site of the ‘rivers of blood’, and it proved almost as significant as its predecessor in the outrage it provoked.

Joseph had long been concerned with what he referred to as ‘cycles of deprivation’, the way in which the stratum of society that would later be termed the underclass was becoming self-perpetuating, dependent on state benefits for generation after generation. ‘A high and rising proportion of children are being born to mothers least fitted to bring children into the world and bring them up,’ he now declared. ‘Some are of low intelligence, most of low educational attainment. They are unlikely to be able to give children the stable emotional background, the consistent combination of love and firmness, which are more important than riches.’

And, in the phrase that damned him, he warned that ‘the balance of our population, our human stock, is threatened’. It was that ‘human stock’ that provided his enemies with the rope with which to hang him.

Was this not, they asked, a call for eugenics, redolent of the policies of Nazi Germany? Not only that, but his argument was unashamedly based on class. He talked of problems in the socio-economic groups four and five, prompting Labour MP Renee Short to leap to the defence of their impugned honour, claiming that ‘it is not those in the fourth and fifth groups who patronize call girls’, a remark that perhaps revealed more about her knowledge of society than about society itself.

Stripped of its emotive phrasing, Joseph’s Edgbaston speech identified an issue that was to become of ever greater significance to policy-makers over the coming decades. But his message was lost amidst the noise, partly at least because he had nothing to offer those on the right, who might otherwise support him, save remedies that they distrusted.

‘The trouble was,’ wrote Margaret Thatcher, his closest ally in the shadow cabinet, ‘that the only short-term answer suggested by Keith for the social problems he outlined was making contraceptives more widely available – and that tended to drive away those who might have been attracted by his larger moral message.’ The birth control pill was still then seen as a totem of the permissive society of the 1960s, and Joseph’s pragmatic endorsement of it (he had made it available nationally on the NHS) failed to resonate with his natural constituency.

Caught between the pill and the pillory, he was assailed on all sides. ‘It’s great fun to see somebody else getting into hot water over a speech,’ chuckled Enoch Powell. ‘I almost wondered if the River Tiber was beginning to roll again.’

But unlike Powell, Joseph was ill-equipped for the media onslaught that ensued. ‘Ever since I made that speech the press have been outside the house,’ he told Thatcher. ‘They have been merciless.’ And, he added, he was no longer prepared to challenge Heath for the leadership of the party; he felt unable to put himself and his family under that kind of pressure permanently.

Four decades back, the defeat of Edward Heath's Conservative Party in two elections in 1974 prompted talk of a change in leadership. There was an obvious candidate, but it turned out he couldn't take the heat. The following account is extracted from my book Crisis? What Crisis?:

And then he threw it away. His first post-election speech was in Edgbaston, not far from the site of the ‘rivers of blood’, and it proved almost as significant as its predecessor in the outrage it provoked.

Joseph had long been concerned with what he referred to as ‘cycles of deprivation’, the way in which the stratum of society that would later be termed the underclass was becoming self-perpetuating, dependent on state benefits for generation after generation. ‘A high and rising proportion of children are being born to mothers least fitted to bring children into the world and bring them up,’ he now declared. ‘Some are of low intelligence, most of low educational attainment. They are unlikely to be able to give children the stable emotional background, the consistent combination of love and firmness, which are more important than riches.’

And, in the phrase that damned him, he warned that ‘the balance of our population, our human stock, is threatened’. It was that ‘human stock’ that provided his enemies with the rope with which to hang him.

Was this not, they asked, a call for eugenics, redolent of the policies of Nazi Germany? Not only that, but his argument was unashamedly based on class. He talked of problems in the socio-economic groups four and five, prompting Labour MP Renee Short to leap to the defence of their impugned honour, claiming that ‘it is not those in the fourth and fifth groups who patronize call girls’, a remark that perhaps revealed more about her knowledge of society than about society itself.

Stripped of its emotive phrasing, Joseph’s Edgbaston speech identified an issue that was to become of ever greater significance to policy-makers over the coming decades. But his message was lost amidst the noise, partly at least because he had nothing to offer those on the right, who might otherwise support him, save remedies that they distrusted.

‘The trouble was,’ wrote Margaret Thatcher, his closest ally in the shadow cabinet, ‘that the only short-term answer suggested by Keith for the social problems he outlined was making contraceptives more widely available – and that tended to drive away those who might have been attracted by his larger moral message.’ The birth control pill was still then seen as a totem of the permissive society of the 1960s, and Joseph’s pragmatic endorsement of it (he had made it available nationally on the NHS) failed to resonate with his natural constituency.

Caught between the pill and the pillory, he was assailed on all sides. ‘It’s great fun to see somebody else getting into hot water over a speech,’ chuckled Enoch Powell. ‘I almost wondered if the River Tiber was beginning to roll again.’

But unlike Powell, Joseph was ill-equipped for the media onslaught that ensued. ‘Ever since I made that speech the press have been outside the house,’ he told Thatcher. ‘They have been merciless.’ And, he added, he was no longer prepared to challenge Heath for the leadership of the party; he felt unable to put himself and his family under that kind of pressure permanently.

The challenge for the next Labour leader (in 1992)

The general election last week is widely said to be reminiscent of 1992. So what were the papers saying at the same stage back then, eight days after John Major's shock result, when the Labour Party was looking for a new leader?

This is how The Times started its editorial on 17 April 1992:

In today's world, that belief in public spending would have him condemned as a left-wing extremist. So too would the trade union support he enjoyed; asked why he hadn't joined the SDP during the Great Schism of the 1980s, he replied: 'I am comfortable with the unions.' And his Scottishness would be regarded with some suspicion.

I'm not sure that any of this represented a response to 'the changing aspirations of the British'. Nonetheless, Black Wednesday came along a few months later, and by the time Smith died in 1994, he had a 20 per cent lead in the polls over the Tories.

This is how The Times started its editorial on 17 April 1992:

Can Labour Win? and Must Labour Lose? were the titles of two bleak books published in 1960, after Labour had lost three elections in a row. Now the same questions are being asked after a run of four defeats.In language that might well sound familiar, the editorial continued:

Labour has failed to respond to the changing aspirations of the British. In the 1980s the Conservative achievement was to make those born working class feel comfortable about wanting to move up in society. Britain may not yet be as socially fluid as America, but the class system is no longer frozen in ice.And it concludes:

Whoever wins the Labour leadership election must prepare his party for the next general election by recognising that the world has changed. The politics of envy have lost their potency. Labour need not lose, but it has to find new friends all over the country, and across all social classes and income groups, before it can win.What actually happened, of course, is that Labour chose John Smith. At the time he was considered to be on the right of Labour, though his enthusiasm for higher taxes was partially blamed for losing the 1992 election.

In today's world, that belief in public spending would have him condemned as a left-wing extremist. So too would the trade union support he enjoyed; asked why he hadn't joined the SDP during the Great Schism of the 1980s, he replied: 'I am comfortable with the unions.' And his Scottishness would be regarded with some suspicion.

I'm not sure that any of this represented a response to 'the changing aspirations of the British'. Nonetheless, Black Wednesday came along a few months later, and by the time Smith died in 1994, he had a 20 per cent lead in the polls over the Tories.

Thursday, 14 May 2015

Revealed: those British values in full

The new government has wasted no time in announcing that it's going to crack down on 'extremism'. Yesterday David Cameron said that it's time to end a culture of 'passive tolerance', in which people have been allowed to think that: 'as long as you obey the law, we will leave you alone.'

Now, we're told, the state should become more interventionist in its promotion of 'British values'.

We've been here before, of course. Back in 2011 Cameron made a speech on exactly the same lines: 'Frankly, we need a lot less of the passive tolerance of recent years and much more active, muscular liberalism.'

It would appear from this that Cameron really has no idea what the phrase 'passive tolerance' means. Maybe his advisers think they've coined it themselves, and are seeking to echo 'passive smoking', in the same way that 'muscular liberalism' echoes 'muscular Christianity'.

But what are these British values that we need to defend with such non-passive muscularity? The following definitions and checklists of Britishness are all quoted in Richard Weight's magnificent book Patriots: National Identity in Britain 1940-2000 (available in paperback).

Michael Balcon, head of Ealing Studios, said in 1945 that his films tried to promote: 'Britain as a leader in social reform, in the defeat of social injustices and a champion of social liberties; Britain as a patron and parent of great writing, painting and music; Britain as a questing explorer, adventurer and trader; Britain as a the home of great industry and craftsmanship; Britain as a mighty military power standing alone and undaunted against terrifying aggression.'

The Festival of Britain programme in 1951 celebrated: 'the fight for religious and civil freedom [and] the idea of parliamentary government; the love of sport and the home; the love of nature and travel; pride in craftsmanship and British eccentricity and humour.'

T.S. Eliot in 1948 suggested: 'Derby Day, Henley Regatta, Cowes, the Twelfth of August, a cup final, the dog races, the pin table, the dart board, Wensleydale cheese, boiled cabbage cut into sections and the music of Elgar.'

Will Cameron's government's initiatives defend these values? No, of course they won't. Social liberties? Civil freedom? Eccentricity? Never heard such nonsense.

Anyway, the truth is that our values are not in the gift of government. We decide them for ourselves.

Now, we're told, the state should become more interventionist in its promotion of 'British values'.

We've been here before, of course. Back in 2011 Cameron made a speech on exactly the same lines: 'Frankly, we need a lot less of the passive tolerance of recent years and much more active, muscular liberalism.'

It would appear from this that Cameron really has no idea what the phrase 'passive tolerance' means. Maybe his advisers think they've coined it themselves, and are seeking to echo 'passive smoking', in the same way that 'muscular liberalism' echoes 'muscular Christianity'.

But what are these British values that we need to defend with such non-passive muscularity? The following definitions and checklists of Britishness are all quoted in Richard Weight's magnificent book Patriots: National Identity in Britain 1940-2000 (available in paperback).

Michael Balcon, head of Ealing Studios, said in 1945 that his films tried to promote: 'Britain as a leader in social reform, in the defeat of social injustices and a champion of social liberties; Britain as a patron and parent of great writing, painting and music; Britain as a questing explorer, adventurer and trader; Britain as a the home of great industry and craftsmanship; Britain as a mighty military power standing alone and undaunted against terrifying aggression.'

The Festival of Britain programme in 1951 celebrated: 'the fight for religious and civil freedom [and] the idea of parliamentary government; the love of sport and the home; the love of nature and travel; pride in craftsmanship and British eccentricity and humour.'

T.S. Eliot in 1948 suggested: 'Derby Day, Henley Regatta, Cowes, the Twelfth of August, a cup final, the dog races, the pin table, the dart board, Wensleydale cheese, boiled cabbage cut into sections and the music of Elgar.'

Will Cameron's government's initiatives defend these values? No, of course they won't. Social liberties? Civil freedom? Eccentricity? Never heard such nonsense.

Anyway, the truth is that our values are not in the gift of government. We decide them for ourselves.

Wednesday, 13 May 2015

Yesterday's News Today: Ed Miliband in 2010

I was looking through some old newspapers yesterday, and stumbled across the Guardian's coverage of Ed Miliband's debut as Labour leader in 2010.

You'll remember that Miliband was elected at the start of the conference week that September, and that a couple of days later he made his first big speech in his new role. The paper invited various figures to comment on the speech:

Tony Benn: 'I supported him for leader, and he's justified my every hope.'

Roy Hattersley: 'Ed Miliband made the speech which, for years, I have wanted a Labour leader to make.'

Jenni Russell: 'The party has chosen the right man. David Miliband could not have spoken like this.'

Seumas Milne: 'This is a long way ahead of Brown, let alone Blair. It also reflects the mainstream centre of public opinion.'

Polly Toynbee: 'Here was a fresh tone of honesty and authenticity ... This was grownup politics.'

Derek Simpson: 'His clear support for the vital role of trade unions is welcome. It has been too long since we heard a Labour leader speak in those terms.'

Anne Perkins: 'warm words, priorities that any progressive would welcome, and no convincing narrative to show what he wanted to do with them.'

Norman Tebbit: 'He had been well rubbed down with snake oil.'

Martin Kettle: 'a political ecumenism which indicates that Miliband's Labour would be seriously open to a centre-left coalition if and when the chance comes.'

Elsewhere, the Independent ran a similar, though less impressive, feature, with comments from Jim Murphy: 'He ensured Labour would remain in the mainstream... He is a serious, deep politician.' And from Dave Prentis: 'These first steps towards refreshing the party are a giant leap towards reconnecting with voters.'

To add to the picture, here's Kevin Maguire in the Daily Mirror: 'His freshness allowed him to pose as the optimist without appearing to be silly.' While the Sun reported Ken Livingstone: 'It was excellent. The only leader's speech in thirty years when I've agreed with every word.'

And some other newspaper comment. The Daily Telegraph leader concluded: 'Labour may yet rue the day they picked the younger Miliband.'

Daniel Finkelstein wrote in The Times: 'The more this week that Mr Miliband has said that he gets it, the less I have believed that he does. The more he said he "understood" voter concerns (rather than shared them) the more I wondered whether he really does.'

Finally back to the Guardian, this is Deborah Orr, writing two days on: 'The first time I watched Ed Miliband's speech to the Labour conference on Tuesday I felt soothed, even grateful. I'd waited a long time to hear a Labour leader say such things after all. Then every time I saw a clip of the speech, that clip seemed slightly absurd... New Labour was a tragedy. New Generation Labour, I'm afraid, seems farcical to me already.'

You'll remember that Miliband was elected at the start of the conference week that September, and that a couple of days later he made his first big speech in his new role. The paper invited various figures to comment on the speech:

Tony Benn: 'I supported him for leader, and he's justified my every hope.'

Roy Hattersley: 'Ed Miliband made the speech which, for years, I have wanted a Labour leader to make.'

Jenni Russell: 'The party has chosen the right man. David Miliband could not have spoken like this.'

Seumas Milne: 'This is a long way ahead of Brown, let alone Blair. It also reflects the mainstream centre of public opinion.'

Polly Toynbee: 'Here was a fresh tone of honesty and authenticity ... This was grownup politics.'

Derek Simpson: 'His clear support for the vital role of trade unions is welcome. It has been too long since we heard a Labour leader speak in those terms.'

Anne Perkins: 'warm words, priorities that any progressive would welcome, and no convincing narrative to show what he wanted to do with them.'

Norman Tebbit: 'He had been well rubbed down with snake oil.'

Martin Kettle: 'a political ecumenism which indicates that Miliband's Labour would be seriously open to a centre-left coalition if and when the chance comes.'

Elsewhere, the Independent ran a similar, though less impressive, feature, with comments from Jim Murphy: 'He ensured Labour would remain in the mainstream... He is a serious, deep politician.' And from Dave Prentis: 'These first steps towards refreshing the party are a giant leap towards reconnecting with voters.'

To add to the picture, here's Kevin Maguire in the Daily Mirror: 'His freshness allowed him to pose as the optimist without appearing to be silly.' While the Sun reported Ken Livingstone: 'It was excellent. The only leader's speech in thirty years when I've agreed with every word.'

And some other newspaper comment. The Daily Telegraph leader concluded: 'Labour may yet rue the day they picked the younger Miliband.'

Daniel Finkelstein wrote in The Times: 'The more this week that Mr Miliband has said that he gets it, the less I have believed that he does. The more he said he "understood" voter concerns (rather than shared them) the more I wondered whether he really does.'

Finally back to the Guardian, this is Deborah Orr, writing two days on: 'The first time I watched Ed Miliband's speech to the Labour conference on Tuesday I felt soothed, even grateful. I'd waited a long time to hear a Labour leader say such things after all. Then every time I saw a clip of the speech, that clip seemed slightly absurd... New Labour was a tragedy. New Generation Labour, I'm afraid, seems farcical to me already.'

Tuesday, 12 May 2015

The priest and the pronoun

Like everyone who reads the Guardian website, I try to avoid the writings of certain contributors, safe in the knowledge that they're just trying to annoy me. In my case it's primarily Jonathan Jones and Giles Fraser. And then last night - for reasons I can't fathom - I found I'd clicked on a piece by Fraser for the first time in months.

He hasn't got any better in the interim. He still annoys me. And he still specialises in the kind of hand-wringing smugness that helped to drive the congregations out of the Church of England.

Writing on Friday, in the immediate aftermath of the election, he says he's 'ashamed to be English', to be living in a country 'that has clearly identified itself as insular, self-absorbed and apparently caring so little for the most vulnerable people among us'. And he wonders: 'Did we just vote for our own narrow concerns and sod the rest?'

Obviously no one's fooled for a second by that 'we'. This is no mea culpa. Readers are expected to understand that the fault lies with others; Fraser, and all decent-minded folk, are motivated solely by concern for 'the most vulnerable people' in our society.

This is part of an all-too-common narrative that anyone who didn't vote for an approved 'progressive' party was merely 'tick[ing] the box of our own self-interest'. (Again, that fraudulent first-person pronoun.) Apparently 'we' sold out the poor on the promise of a mess of pottage some way down the road.

By the same token, I suppose, one could argue that those in receipt of benefits, or those employed by the state, might have voted Labour in the expectation that their income would thus be better protected. They were sufficiently selfish that they demanded others pay higher taxes on their behalf.

Both positions are nonsense, of course. When casting a vote, most people (I believe) find that self-interest co-exists with other considerations, including an assessment of which of the limited alternatives on offer might be in the national interest.

And last week around half of those who voted in the United Kingdom opted for the Conservative Party or for Ukip, parties with whom Fraser has little sympathy, and of which he has little understanding.

One would have to be very arrogant indeed to conclude that - unlike oneself - those voters don't care about anyone else. It may well be that they believe 'the most vulnerable' can be better helped in a wealthy country than in a poor one, and therefore opted against parties who they felt would harm the economy. Even if you think their judgement is wrong, that doesn't mean it was made in bad faith.

Nor do people vote for the totality of a party's programme. Many, perhaps millions, who voted Conservative will have done so despite disagreeing with proposed cuts to disability benefits. Just as many, perhaps millions, will have voted Labour despite disagreeing with their promise to 'control immigration'.

Why am I bothering with Fraser, the kind of Christian who believes that the existence of charity is an indictment of society?

Well, because I've had a couple of people tell me that my post-election pieces on this blog are unnecessarily harsh on Labour and the Greens, and unreasonably positive about the Conservatives and Ukip. Which may be true but, unlike Fraser, I'm not interested in seeking comfort by denouncing all those who stray beyond the 'progressive' pale.

The truth is that the Left lost very badly last week, and the Right won. Even if you put together the Labour and the SNP votes, they still didn't reach the total cast for the Conservatives. That needs examining and, if possible, explaining. And in pursuit of that, one should strive for objectivity, rather than settle for accusations.

To misquote Karl Marx: Some historians have tried to change the world in various ways; the point is to understand it.

He hasn't got any better in the interim. He still annoys me. And he still specialises in the kind of hand-wringing smugness that helped to drive the congregations out of the Church of England.

Writing on Friday, in the immediate aftermath of the election, he says he's 'ashamed to be English', to be living in a country 'that has clearly identified itself as insular, self-absorbed and apparently caring so little for the most vulnerable people among us'. And he wonders: 'Did we just vote for our own narrow concerns and sod the rest?'

Obviously no one's fooled for a second by that 'we'. This is no mea culpa. Readers are expected to understand that the fault lies with others; Fraser, and all decent-minded folk, are motivated solely by concern for 'the most vulnerable people' in our society.

This is part of an all-too-common narrative that anyone who didn't vote for an approved 'progressive' party was merely 'tick[ing] the box of our own self-interest'. (Again, that fraudulent first-person pronoun.) Apparently 'we' sold out the poor on the promise of a mess of pottage some way down the road.

By the same token, I suppose, one could argue that those in receipt of benefits, or those employed by the state, might have voted Labour in the expectation that their income would thus be better protected. They were sufficiently selfish that they demanded others pay higher taxes on their behalf.

Both positions are nonsense, of course. When casting a vote, most people (I believe) find that self-interest co-exists with other considerations, including an assessment of which of the limited alternatives on offer might be in the national interest.

And last week around half of those who voted in the United Kingdom opted for the Conservative Party or for Ukip, parties with whom Fraser has little sympathy, and of which he has little understanding.

One would have to be very arrogant indeed to conclude that - unlike oneself - those voters don't care about anyone else. It may well be that they believe 'the most vulnerable' can be better helped in a wealthy country than in a poor one, and therefore opted against parties who they felt would harm the economy. Even if you think their judgement is wrong, that doesn't mean it was made in bad faith.

Nor do people vote for the totality of a party's programme. Many, perhaps millions, who voted Conservative will have done so despite disagreeing with proposed cuts to disability benefits. Just as many, perhaps millions, will have voted Labour despite disagreeing with their promise to 'control immigration'.

Why am I bothering with Fraser, the kind of Christian who believes that the existence of charity is an indictment of society?

Well, because I've had a couple of people tell me that my post-election pieces on this blog are unnecessarily harsh on Labour and the Greens, and unreasonably positive about the Conservatives and Ukip. Which may be true but, unlike Fraser, I'm not interested in seeking comfort by denouncing all those who stray beyond the 'progressive' pale.

The truth is that the Left lost very badly last week, and the Right won. Even if you put together the Labour and the SNP votes, they still didn't reach the total cast for the Conservatives. That needs examining and, if possible, explaining. And in pursuit of that, one should strive for objectivity, rather than settle for accusations.

To misquote Karl Marx: Some historians have tried to change the world in various ways; the point is to understand it.

Monday, 11 May 2015

David Cameron: chillaxing to victory

In 2005, following a third successive election defeat, the Conservative Party staged a beauty contest for those who wished to succeed Michael Howard as leader. Up until that morning, the front-runner had been David Davis, but by the time all five candidates had made their 20-minute speeches, he'd been overtaken by David Cameron.

Amongst those who had their minds changed was me. I rated Davis highly at this stage, largely on the strength of a gig he did with Tony Benn at the Royal Albert Hall in 2002. Benn was then at the peak of his popularity as a lovable elder statesman, and for a Conservative to have the nerve to go head-to-head with him in front of an audience that was guaranteed to be 99 per cent anti-Tory showed, I thought, considerable bottle and self-confidence. He was also very good on the night.

Unfortunately he wasn't very good at that 2005 conference, while Cameron was brilliant. Maybe - I've often had cause to think in the last ten years - I was dazzled by a smoke-and-mirrors act, but my immediate response was to predict to the person with whom I was watching on TV that Cameron would win the leadership and would go on to win the next two general elections.

As I say, maybe I was caught up in the heat of the moment. In the final poll, the party members voted for Cameron over Davis in a ratio of two to one, but come 2010 the country did not. He failed to win the election, despite facing only a badly wounded Gordon Brown, a man whose most noteworthy contribution to the campaign was to insult a supporter for her alleged bigotry.

Now, however, Cameron has actually won an election, and I feel my original judgement was sort of vindicated.

This has been a spectacular victory, though not quite as wondrous as some are claiming. The Conservatives' share of the vote went up, but turnout was still poor and Cameron persuaded just 24.4 per cent of the registered electorate to vote for him. This was, however, better than the 23.5 per cent he achieved last time round (itself an improvement on Labour's 21.6 per cent in 2005).

So I wanted to make a couple of points about Cameron.

The first is something that I explored at greater length in an article on the twenty-first anniversary of Black Wednesday. This is a photograph of Norman Lamont, then chancellor of the exchequer, announcing Britain's humiliating withdrawal from the exchange rate mechanism in September 1992:

And there, off to one side, is his 25-year-old adviser and speech writer, David Cameron.

Cameron, I wrote, 'witnessed at close quarters the spectacular implosion of a party that once believed it was predestined to power'. I suggested that this is perhaps why he always seems so relaxed in a crisis. Similarly George Osborne, who was at Douglas Hogg's side in the BSE disaster of 1996. These people had experienced such dreadful political depths in their early years that very little was going to faze them.

Ed Miliband and Ed Balls, on the other hand were New Labour advisers in the 1990s, at a time when the party was already coasting into government. They had no such baptism of fire.

When Cameron became leader in 2005, it was clear that his job was, in the cliché of the time, to 'decontaminate the Tory brand'. The early efforts were clumsy and gimmicky: hugging hoodies and huskies, demonstrating his green credentials by installing a windmill on his roof and cycling to work (followed by a car, carrying his papers).

Then he got blown off course by the bankers' recession. No longer, it appeared, was sunshine going to win the day. The concept of the Big Society withered on the vine (though it's actually very good and the Labour Party should take it back).

Instead, the attempt to modernise the party seemed to consist of little more than the sudden, unpromised introduction of same-sex marriages. It didn't seem like very much - essentially a new name for civil partnerships - but actually it turned out to do the job really rather well.

Because the success of same-sex marriages lay not in the legislation itself, but in the way that it provoked a mass exodus from the party. Some constituency organisations claimed to have lost up to half their members as a result of the policy.

This was, most commentators agreed, disastrous for Cameron. But it wasn't. In one fell blow he'd cleared out large numbers of the 'fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists', as he'd described Ukip back in 2006. Many of them, of course, went straight over to Ukip, giving that party a huge boost in membership and popularity.

Less noticed was the effect on the Conservative Party itself, now smaller but - from Cameron's perspective - much better looking. It has become difficult to denounce the Tories as racist, sexist, homophobic and still retain any credibility as a political observer. The party that embraced economic liberalism in the 1980s has accepted the social liberalism that spread across Britain in the 1990s.

The election results this week saw Cameron increase the Conservative share of the vote, largely at the expense of the Liberal Democrats. All those right-wing commentators like Simon Heffer and Charles Moore who had insisted that the Cameron project was misguided, that he shouldn't be trying to appeal to the liberal vote (sometimes even suggesting he form an electoral pact with Ukip) - they turned out to be completely wrong.

There are many other commentators for whom the Tory brand cannot ever be sufficiently decontaminated, but it turns out that he's done enough. Not enough for those in the long-derided 'metropolitan elite' of course, those who follow in the pioneering footsteps of the delegate to the 1982 SDP conference, excitedly proclaiming: 'There may be minorities we have not yet discovered.' But enough for the rest of the country.

The achievement of Tony Blair in the mid-1990s was to make the Labour Party a safe home for ex-Tory voters. If Cameron hasn't quite reciprocated that achievement, he has gone some way towards it. There were many disillusioned Liberal Democrats, and even some lifelong Labour supporters, who simply couldn't countenance Ed Miliband and who felt just about safe enough to turn to vote Conservative for the first time ever, despite grave reservations over Tory policy.

As all the polls showed, Cameron's ratings outstripped his party's; Miliband's trailed his.

The Left need to get used to the idea that Cameron and Osborne have changed the Conservative Party for good. A new line of attack is needed.

One final thought. There is much talk of this election resembling 1992 when John Major won a slender majority and then ran into trouble with his own party over Europe. And look what's coming next, say the columnists: it's a European referendum and history could repeat itself.

I think this unlikely. If Ukip had got, say, five MPs they might have formed a rival pole of attraction for Eurosceptic Tory members, and there might have been defections over the referendum arrangements. Then Cameron would have had trouble. That might still happen if there are a few by-elections that allow Ukip to boost their numbers, but I doubt it. And Douglas Carswell does not in himself constitute a rival pole of attraction.

In any event, Cameron is much more in tune with the mood of his party than Major was. He remembers all too well the damage that Europe did to the Tories in the 1990s. Most importantly, he doesn't face the same problem that afflicted his predecessor.

Because Major's real grief over Europe was not to be found amongst the 'bastards' on his own backbenches; it lay in the House of Lords. There lurked the malign influence of Margaret Thatcher, the deposed but still powerful ex-leader, constitutionally unable to keep herself from interfering, from stirring up trouble, from seeking to undermine her successor as he tried to get the Maastricht Treaty through Parliament.

As I wrote in my book A Classless Society:

Amongst those who had their minds changed was me. I rated Davis highly at this stage, largely on the strength of a gig he did with Tony Benn at the Royal Albert Hall in 2002. Benn was then at the peak of his popularity as a lovable elder statesman, and for a Conservative to have the nerve to go head-to-head with him in front of an audience that was guaranteed to be 99 per cent anti-Tory showed, I thought, considerable bottle and self-confidence. He was also very good on the night.

Unfortunately he wasn't very good at that 2005 conference, while Cameron was brilliant. Maybe - I've often had cause to think in the last ten years - I was dazzled by a smoke-and-mirrors act, but my immediate response was to predict to the person with whom I was watching on TV that Cameron would win the leadership and would go on to win the next two general elections.

As I say, maybe I was caught up in the heat of the moment. In the final poll, the party members voted for Cameron over Davis in a ratio of two to one, but come 2010 the country did not. He failed to win the election, despite facing only a badly wounded Gordon Brown, a man whose most noteworthy contribution to the campaign was to insult a supporter for her alleged bigotry.

Now, however, Cameron has actually won an election, and I feel my original judgement was sort of vindicated.

This has been a spectacular victory, though not quite as wondrous as some are claiming. The Conservatives' share of the vote went up, but turnout was still poor and Cameron persuaded just 24.4 per cent of the registered electorate to vote for him. This was, however, better than the 23.5 per cent he achieved last time round (itself an improvement on Labour's 21.6 per cent in 2005).

So I wanted to make a couple of points about Cameron.

The first is something that I explored at greater length in an article on the twenty-first anniversary of Black Wednesday. This is a photograph of Norman Lamont, then chancellor of the exchequer, announcing Britain's humiliating withdrawal from the exchange rate mechanism in September 1992:

And there, off to one side, is his 25-year-old adviser and speech writer, David Cameron.

Cameron, I wrote, 'witnessed at close quarters the spectacular implosion of a party that once believed it was predestined to power'. I suggested that this is perhaps why he always seems so relaxed in a crisis. Similarly George Osborne, who was at Douglas Hogg's side in the BSE disaster of 1996. These people had experienced such dreadful political depths in their early years that very little was going to faze them.

Ed Miliband and Ed Balls, on the other hand were New Labour advisers in the 1990s, at a time when the party was already coasting into government. They had no such baptism of fire.

When Cameron became leader in 2005, it was clear that his job was, in the cliché of the time, to 'decontaminate the Tory brand'. The early efforts were clumsy and gimmicky: hugging hoodies and huskies, demonstrating his green credentials by installing a windmill on his roof and cycling to work (followed by a car, carrying his papers).

Then he got blown off course by the bankers' recession. No longer, it appeared, was sunshine going to win the day. The concept of the Big Society withered on the vine (though it's actually very good and the Labour Party should take it back).

Instead, the attempt to modernise the party seemed to consist of little more than the sudden, unpromised introduction of same-sex marriages. It didn't seem like very much - essentially a new name for civil partnerships - but actually it turned out to do the job really rather well.

Because the success of same-sex marriages lay not in the legislation itself, but in the way that it provoked a mass exodus from the party. Some constituency organisations claimed to have lost up to half their members as a result of the policy.

This was, most commentators agreed, disastrous for Cameron. But it wasn't. In one fell blow he'd cleared out large numbers of the 'fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists', as he'd described Ukip back in 2006. Many of them, of course, went straight over to Ukip, giving that party a huge boost in membership and popularity.

Less noticed was the effect on the Conservative Party itself, now smaller but - from Cameron's perspective - much better looking. It has become difficult to denounce the Tories as racist, sexist, homophobic and still retain any credibility as a political observer. The party that embraced economic liberalism in the 1980s has accepted the social liberalism that spread across Britain in the 1990s.

The election results this week saw Cameron increase the Conservative share of the vote, largely at the expense of the Liberal Democrats. All those right-wing commentators like Simon Heffer and Charles Moore who had insisted that the Cameron project was misguided, that he shouldn't be trying to appeal to the liberal vote (sometimes even suggesting he form an electoral pact with Ukip) - they turned out to be completely wrong.

There are many other commentators for whom the Tory brand cannot ever be sufficiently decontaminated, but it turns out that he's done enough. Not enough for those in the long-derided 'metropolitan elite' of course, those who follow in the pioneering footsteps of the delegate to the 1982 SDP conference, excitedly proclaiming: 'There may be minorities we have not yet discovered.' But enough for the rest of the country.

The achievement of Tony Blair in the mid-1990s was to make the Labour Party a safe home for ex-Tory voters. If Cameron hasn't quite reciprocated that achievement, he has gone some way towards it. There were many disillusioned Liberal Democrats, and even some lifelong Labour supporters, who simply couldn't countenance Ed Miliband and who felt just about safe enough to turn to vote Conservative for the first time ever, despite grave reservations over Tory policy.

As all the polls showed, Cameron's ratings outstripped his party's; Miliband's trailed his.

The Left need to get used to the idea that Cameron and Osborne have changed the Conservative Party for good. A new line of attack is needed.

One final thought. There is much talk of this election resembling 1992 when John Major won a slender majority and then ran into trouble with his own party over Europe. And look what's coming next, say the columnists: it's a European referendum and history could repeat itself.

I think this unlikely. If Ukip had got, say, five MPs they might have formed a rival pole of attraction for Eurosceptic Tory members, and there might have been defections over the referendum arrangements. Then Cameron would have had trouble. That might still happen if there are a few by-elections that allow Ukip to boost their numbers, but I doubt it. And Douglas Carswell does not in himself constitute a rival pole of attraction.

In any event, Cameron is much more in tune with the mood of his party than Major was. He remembers all too well the damage that Europe did to the Tories in the 1990s. Most importantly, he doesn't face the same problem that afflicted his predecessor.

Because Major's real grief over Europe was not to be found amongst the 'bastards' on his own backbenches; it lay in the House of Lords. There lurked the malign influence of Margaret Thatcher, the deposed but still powerful ex-leader, constitutionally unable to keep herself from interfering, from stirring up trouble, from seeking to undermine her successor as he tried to get the Maastricht Treaty through Parliament.

As I wrote in my book A Classless Society:

Thatcher's behaviour during Major's premiership was even worse than that of Edward Heath during her own time in office. Heath had been unstinting in his disapproval as he remained stubbornly on the backbenches ('like a sulk made flesh,' in the words of journalist Edward Pearce), but he hadn't actively engaged in plotting against her. But then, as a minister told the BBC's John Cole: 'She was always criticising the government when she led it, so why expect her to change now?'The EU referendum won't all be smooth sailing, but it'll be less choppy than Major's trip back from Maastricht. And easier than Cameron's rite of passage on Black Wednesday.

Sunday, 10 May 2015

A tale of some minor parties

A week or so back, I predicted that one consequence of the election would be the resignations of Nigel Farage and Nick Clegg as the leaders of, respectively, Ukip and the Liberal Democrats. I also predicted that Natalie Bennett would not resign as leader of the Green Party of England and Wales.

These things having now come to pass, it's time to evaluate them.

Starting with the last first, Bennett should have the decency to go immediately. She has proved herself to be completely useless as a leader. The Greens had a dreadful election, and much of the blame for that rests with her.

The party achieved less than 4 per cent of the vote. Under most sensible forms of proportional representation, the bar for securing seats is set at 5 per cent. Frankly they're fortunate that first-past-the-post came to their rescue and gave them an MP.

Yet the opportunity was unquestionably there for the Greens: lots of airtime and visibility, a weak Labour leadership, a widespread dissatisfaction with mainstream politics. A breakthrough of sorts was possible. Obviously not in terms of winning large numbers of seats, but even without representation, a minor party can still have an influence, can help to shape the political agenda.

You only need look to Ukip. At a time when they had no MPs at all, they were still capable of scaring the British prime minister into promising a referendum when he didn't want one, and panicking the Labour Party into saying they'd 'get tough' on immigration, when we knew they wouldn't.

So what did Bennett do? She joined in the chorus of 'the Tories are mean and nasty'. Well, if you believed that, then you should have done the sensible thing and voted for a party capable of removing the Conservatives from office. Which is, indeed, what the vast majority of those opposed to the Tories actually did.

At a constituency level, things may have been different, but on the national stage Bennett offered nothing at all that was distinctive. One brief mention in a leaders' debate of climate change and vanishing species, and that was it. At a time when fracking offers a perfect way of linking the local with the global, there was only silence.

It is, of course, more difficult to get attention for environmental issues at a time of economic hardship, but this is far from a new problem. I wrote about it in Crisis? What Crisis?, my book on the 1970s. There's been plenty of time to work out a strategy for such a situation.

The Greens are one of the few parties who actually have a USP. Yet they didn't exploit it. Instead there was a manifesto and a platform full of policies on an absurd range of issues that were entirely irrelevant, including the stupidity over copyright, to which I drew attention a while back. (And which subsequently annoyed the hell out of a lot of creative people who were sympathetic to the party.)

Why? Where's the benefit in burying your brand? Why allow your core message to be lost amidst a welter of questions about a tax policy you will never have a chance to implement?

One other point, which most people are (quite rightly) too polite and decent to say out loud: the voice was wrong. The British public didn't warm to being waffled at in an Australian accent. Obviously it shouldn't matter, but it does.

In short, Bennett should go.

So too should Farage. He's left open the possibility of coming back from his holidays and standing again for the Ukip leadership, but he should resist the temptation. The party is better off without him now.

He has been an extraordinary figure who has over-achieved on a spectacular scale. In many ways, he was the story of the Coalition years, conducting a brilliant guerrilla campaign against Westminster. (Do I need to point out that I'm talking about technique not policies? I do hope not.) I went to one of his EU debates with Nick Clegg and he was a superb performer - committed Europhiles were coming out of the hall saying how good he was.

But he still has to go.

When Ukip won the elections for the European Parliament a year ago, I wrote that they'd reached their high-water mark. If they were ever to go any further, I suggested, they needed to thank Farage for all his work and ask him to step down. He'd taken them as far as he possibly could. My comparison was with Ian Holloway, a colourful, charming and competent manager who got Blackpool Football Club to the Premier League, but couldn't keep them there.

My argument was that if Ukip wanted to secure - let alone go beyond - the 4.4 million votes they achieved last year, they had to make serious inroads into Labour heartlands, and Farage was probably not the man for that. He did pretty well this week, but the party fell to 3.9 million votes on a far higher turnout. It could have been better if he'd gone last year. Now it's probably too late, and decline is (I think) inevitable.

Ukip are, as normal with third parties, an odd coalition of the disgruntled and the idealistic from all points of the political compass.

There are two broad bases of support: the Eurosceptic deserters from the Conservative Party and the disillusioned white working-class who feel abandoned by Labour. These are represented by Douglas Carswell and Paul Nuttall respectively, and I assume that they will be the two candidates in a leadership election. I also assume that Carswell will win, to the detriment of the party's electoral interests.

The alternative is Suzanne Evans, currently the acting leader, who would be their best choice of all. And since I think that, I don't expect her to get the job on a permanent basis.

Their moment has passed, but they leave behind an example of how to make a difference. Why is there no Left party that can do this?

And so, finally, to Nick Clegg.

What can one say? Well, firstly, that he made exactly the right decision in 2010. The Lib Dems, and before them the Liberals, had always banged on about coalition government being a good thing. They were offered it, and they accepted. To do otherwise would have been foolish.

Some people complained that Clegg would have sold his own mother to get power, but that judgement seemed a little harsh. After all, he did join the Lib Dems, which isn't traditionally the way to achieve high office. Given the state of modern politics, he could have fitted perfectly comfortably into the modern Conservative or Labour Parties, but he chose the road less travelled.

As the junior partner in the Coalition, the Lib Dems proved surprisingly effective at government. They got through key policies like the pupil premium and raising the threshold for income tax; even the tuition fees increase - damaging though it was - had a logic, if they'd only had the sense to call it a time-limited graduate tax.